|

"As for me, I am rather often uneasy in my mind, because I think that my life has not been calm enough; all those bitter disappointments, adversities, changes keep me from developing fully and naturally in my artistic career."

Vincent van Gogh |

|

The biography below is by no means a complete and comprehensive exploration of the life of Vincent van Gogh. Instead, it's merely an overview of some of the important events in the chronicle of Van Gogh's life. In my "Books" section I have a page devoted specifically to Van Gogh biographies and there I recommend some of the best. First and foremost among these is Jan Hulsker's Vincent and Theo Van Gogh: A Dual Biography--highly recommended.

For a chronological summary of Van Gogh's life, please refer to the Chronology section.

Vincent van Gogh was born in Groot Zundert, The Netherlands on 30 March 1853. Van Gogh's birth came one year to the day after his mother gave birth to a first, stillborn child--also named Vincent. There has been much speculation about Vincent van Gogh suffering later psychological trauma as a result of being a "replacement child" and having a deceased brother with the same name and same birth date. This theory remains unsubstantiated, however, and there is no actual historical evidence to support it.

Van Gogh was the son of Theodorus van Gogh (1822-85), a pastor of the Dutch Reformed Church, and Anna Cornelia Carbentus (1819-1907). Unfortunately there is virtually no information about Vincent van Gogh's first ten years. Van Gogh attended a boarding school in Zevenbergen for two years and then went on to attend the King Willem II secondary school in Tilburg for two more. At that time, in 1868, Van Gogh left his studies at the age of 15 and never returned.

In 1869 Vincent van Gogh joined the firm Goupil & Cie., a firm of art dealers in The Hague. The Van Gogh family had long been associated with the art world--Vincent's uncles, Cornelis ("Uncle Cor") and Vincent ("Uncle Cent"), were art dealers. His younger brother, Theo, spent his adult life working as an art dealer and, as a result, had a tremendous influence on Vincent's later career as an artist.

Vincent was relatively successful as an art dealer and stayed with Goupil & Cie. for seven more years. In 1873 he was transferred to the London branch of the company and quickly became enamoured with the cultural climate of England. In late August, Vincent moved to 87 Hackford Road and boarded with Ursula Loyer and her daughter Eugenie. Vincent is said to have been romantically interested in Eugenie, but many early biographers mistakenly misname Eugenie for her mother, Ursula. To add to the decades-long confusion over the names, recent evidence suggests that Vincent wasn't in love with Eugenie at all, but rather a Dutch woman named Caroline Haanebeek. The truth remains inconclusive.

Vincent van Gogh would remain in London for two more years. During that time he visited the many art galleries and museums and became a great admirer of British writers such as George Eliot and Charles Dickens. Van Gogh was also a great admirer of the British engravers whose works illustrated such magazines as The Graphic. These illustrations inspired and influenced Van Gogh in his later life as an artist.

The relationship between Vincent and Goupil's became more strained as the years passed and in May of 1875 he was transferred to the Paris branch of the firm. It became clear as the year wore on that Vincent was no longer happy dealing in paintings that had little appeal for him in terms of his own personal tastes. Vincent left Goupil's in late March, 1876 and decided to return to England where his two years there had been, for the most part, very happy and rewarding.

In April Vincent van Gogh began teaching at Rev. William P. Stokes' school in Ramsgate. He was responsible for 24 boys between the ages of 10 and 14. His letters suggest that Vincent enjoyed teaching. After that he began teaching at another school for boys, this one lead by Rev. T. Slade Jones in Isleworth. In his spare time Van Gogh continued to visit galleries and admire the many great works of art he found there. He also devoted himself to his Bible study--spending many hours reading and rereading the Gospel. The summer of 1876 was truly a time of religious transformation for Vincent van Gogh. Although raised in a religious family, it wasn't until this time that he seriously began to consider devoting his life to the Church.

As a means of making a transition from teacher to clergyman, Vincent requested that Rev. Jones give him more responsibilities specific to the clergy. Jones agreed and Vincent began to speak at prayer meetings held within the parish of Turnham Green. These talks served as a means of preparing Vincent for the task which he had long anticipated: his first Sunday sermon. Although Vincent was enthusiastic about his prospects as a minister, his sermons were somewhat lackluster and lifeless. Like his father, Vincent had a passion for preaching, but lacked a gripping and passionate delivery.

Undeterred, Vincent van Gogh chose to remain in The Netherlands after visiting his family over Christmas. After working briefly in a bookshop in Dordrecht in early 1877, Vincent left for Amsterdam on 9 May to prepare himself for the admission examination to the university where he was to study theology. Vincent received lessons in Greek, Latin and mathematics, but his lack of proficiency ultimately compelled him to abandon his studies after fifteen months. Vincent later described this period as "the worst time of my life". In November Vincent failed to qualify for the mission school in Laeken after a three month trial period. Never one to be swayed by adversity, Vincent van Gogh eventually made arrangements with the Church to begin a trial period preaching in one of the most inhospitable and impoverished regions in western Europe: the coal mining district of The Borinage, Belgium.

In January, 1879 Vincent began his duties preaching to the coal miners and their families in the mining village of Wasmes. Vincent felt a strong emotional attachment to the miners. He sympathized with their dreadful working conditions and did his best, as their spiritual leader, to ease the burden of their lives. Unfortunately, this altruistic desire would reach somewhat fanatical proportions when Vincent began to give away most of his food and clothing to the poverty-stricken people under his care. Despite Vincent's noble intentions, representatives of the Church strongly disapproved of Van Gogh's asceticism and dismissed him from his post in July. Refusing to leave the area, Van Gogh moved to an adjacent village, Cuesmes, and remained there in abject poverty. For the next year Vincent struggled to live from day to day and, though not able to help the village people in any official capacity as a clergyman, he nevertheless chose to remain a member of their community. One day Vincent felt compelled to visit the home of Jules Breton, a French painter he greatly admired, so with only ten francs in his pocket he walked the entire 70 kilometers to Courri res, France, to see Breton. Upon arriving, however, Vincent was too timid to knock and returned to Cuesmes utterly discouraged.

In January, 1879 Vincent began his duties preaching to the coal miners and their families in the mining village of Wasmes. Vincent felt a strong emotional attachment to the miners. He sympathized with their dreadful working conditions and did his best, as their spiritual leader, to ease the burden of their lives. Unfortunately, this altruistic desire would reach somewhat fanatical proportions when Vincent began to give away most of his food and clothing to the poverty-stricken people under his care. Despite Vincent's noble intentions, representatives of the Church strongly disapproved of Van Gogh's asceticism and dismissed him from his post in July. Refusing to leave the area, Van Gogh moved to an adjacent village, Cuesmes, and remained there in abject poverty. For the next year Vincent struggled to live from day to day and, though not able to help the village people in any official capacity as a clergyman, he nevertheless chose to remain a member of their community. One day Vincent felt compelled to visit the home of Jules Breton, a French painter he greatly admired, so with only ten francs in his pocket he walked the entire 70 kilometers to Courri res, France, to see Breton. Upon arriving, however, Vincent was too timid to knock and returned to Cuesmes utterly discouraged.

It was then that Vincent began to draw the miners and their families, chronicling their harsh conditions. It was during this pivotal time that Vincent van Gogh chose his next and final career: as an artist.

Beginnings as an Artist

In autumn of 1880, after more than a year living as a pauper in the Borinage, Vincent left for Brussels to begin his art studies. Vincent was inspired to begin these studies as a result of financial help from his brother, Theo. Vincent and Theo had always been close as children and throughout most of their adult lives maintained an ongoing and poignantly revealing correspondence. It is these letters, in total more than 700 extant, which form most of our knowledge of Van Gogh's perceptions about his own life and works.

1881 would prove to be a turbulent year for Vincent van Gogh. Vincent applied for study at the Ecole des Beaux-Art in Brussels, although the biographers Hulsker and Tralbaut conflict with regards to the details. Tralbaut suggests a short and unremarkable tenure with the school, whereas Hulsker maintains that Vincent's application for admission was never accepted. Whatever the case, Vincent continued drawings lessons on his own, taking examples from such books as Travaux des champs by Jean-Fran ois Millet and Cours de dessin by Charles Bargue. In the summer Vincent was once again living with his parents, now situated in Etten, and during that time he met his cousin Cornelia Adriana Vos-Stricker (Kee). Kee (1846-1918) had been recently widowed and was raising a young son on her own. Vincent fell in love with Kee and was devastated when she rejected his advances. The unfortunate episode concluded with one of the most memorable incidents in Van Gogh's life. After being spurned by Kee, Vincent decided to confront her at her parents house. Kee's father refused to let Vincent see his daughter and Vincent, ever determined, put his hand over the funnel of an oil lamp, intentionally burning himself. Vincent's intent was to hold his hand over the flame until he was allowed to see Kee. Kee's father quickly defused the situation by simply blowing out the lamp and Vincent left the house humiliated.

Despite emotional setbacks with Kee and personal tensions with his father, Vincent found some encouragement from Anton Mauve (1838-88), his cousin by marriage. Mauve had established himself as a successful artist, and from his home in The Hague, supplied Vincent with his first set of watercolours--thus giving Vincent his initial introduction to working in colours. Vincent was a great admirer of Mauve's works and was deeply grateful for any instruction that Mauve was able to provide. Their relationship was a pleasant one, but would suffer due to tensions brought about when Vincent began living with a prostitute.

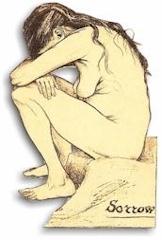

Vincent van Gogh met Clasina Maria Hoornik (1850-1904) in late February 1882, in The Hague. Already pregnant with her second child when Van Gogh met her, this woman, known as "Sien", moved in with Vincent shortly afterward. Vincent lived with Sien for the next year and a half. Their relationship was a stormy one, partly due to both of their volatile personalities and also because of the strain of living in complete poverty. Vincent's letters to Theo show him to be devoted to Sien and especially her children, but his art was always his first passion--to the exclusion of all other concerns, including food. Sien and her children posed for dozens of drawings for Vincent, and his talents as an artist grew considerably during this period. His early, more primitive drawings of the coal miners in the Borinage made way for far more refined and emotion-laden works. In the drawing Sien, Sitting on a Basket, with a Girl, for example, Vincent masterfully depicts quiet domesticity, as well as an underlying sense of despair--feelings which would truly define Van Gogh's 19 months living with Sien.

Vincent van Gogh met Clasina Maria Hoornik (1850-1904) in late February 1882, in The Hague. Already pregnant with her second child when Van Gogh met her, this woman, known as "Sien", moved in with Vincent shortly afterward. Vincent lived with Sien for the next year and a half. Their relationship was a stormy one, partly due to both of their volatile personalities and also because of the strain of living in complete poverty. Vincent's letters to Theo show him to be devoted to Sien and especially her children, but his art was always his first passion--to the exclusion of all other concerns, including food. Sien and her children posed for dozens of drawings for Vincent, and his talents as an artist grew considerably during this period. His early, more primitive drawings of the coal miners in the Borinage made way for far more refined and emotion-laden works. In the drawing Sien, Sitting on a Basket, with a Girl, for example, Vincent masterfully depicts quiet domesticity, as well as an underlying sense of despair--feelings which would truly define Van Gogh's 19 months living with Sien.

1883 was another year of transition for Van Gogh: both in his personal life and in his role as an artist. Vincent began to experiment with oil paints in 1882, but it wasn't until 1883 that he worked in this medium more and more frequently. As his drawing and painting skills advanced, his relationship with Sien deteriorated and they parted ways in September. As with his failure in The Borinage, Vincent would spend his time recovering from this failed relationship in isolation. With much regret, particularly because of his feelings for Sien's children, Vincent left The Hague in mid-September to travel to Drenthe, a somewhat desolate district in The Netherlands. For the next six weeks Vincent lived a rather nomadic life, moving throughout the region and drawing and painting the remote landscape and its inhabitants.

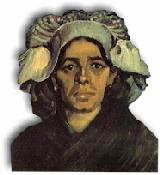

Once again, Vincent returned to his parents' home, now in Nuenen, in late 1883. Throughout the following year Vincent van Gogh continued to refine his craft. He produced dozens of paintings and drawings during this period: weavers, spinners and other portraits. The local peasants proved to be his favourite subjects--in part because Van Gogh felt a strong affinity toward the poor working labourers and partly because he was such an admirer of the painter Millet who himself produced sensitive and compassionate paintings of workers in the fields. Vincent's romantic life took yet another dramatic and unhappy turn that summer. Margot Begemann (1841-1907), whose family lived next door to Vincent's parents, had been in love with Vincent, and the emotional upheaval of the relationship lead her to attempt suicide by poison. Vincent was greatly distraught over the incident. Margot eventually recovered, but the episode upset Vincent a great deal and he referred to it in his letters on a number of occasions.

Turning Point 1885: The First Great Works

In the early months of 1885 Van Gogh continued his series of portraits of peasants. Vincent viewed these as "studies", works which would continue to refine his craft in preparation for his most ambitious work to date. Vincent laboured throughout March and April on these studies, briefly distracted from his work by the death of his father on 26 March. Vincent and his father had maintained a severely strained relationship over the last few years and, while certainly not happy about his father's death, Vincent was quite emotionally detached and continued his work.

All the years of hard work, of continually refining his technique and learning to work in new media--all served as stepping stones toward the production of Vincent van Gogh's first great painting: The Potato Eaters.

All the years of hard work, of continually refining his technique and learning to work in new media--all served as stepping stones toward the production of Vincent van Gogh's first great painting: The Potato Eaters.

Vincent worked on The Potato Eaters throughout April of 1885. He had produced various drafts in preparation of the final, large oil on canvas version. The Potato Eaters is acknowledged to be Vincent van Gogh's first true masterpiece and he was encouraged by the outcome. Although angered and upset by any criticism of the work (Vincent's friend and fellow artist, Anthon van Rappard (1858-1892), disliked the work and his comments would prompt Vincent to end their friendship), Vincent was pleased with the result and thus began a new, more confident and technically accomplished phase of his career.

Van Gogh continued to work throughout 1885, but once again became restless and in need of new stimulation. He enrolled briefly in the Academy in Antwerp in early 1886, but left it about four weeks later feeling stifled by the narrow and rigid approach of the instructors. As he demonstrated frequently throughout his life, Vincent felt that formal study was a poor substitute for practical work. Vincent had worked for five difficult years to hone his talents as an artist and with the creation of The Potato Eaters he proved himself a first-rate painter. But Vincent continually sought to better himself, to acquire new ideas and explore new techniques as a means of becoming the artist he truly aspired to be. In The Netherlands he had accomplished as much as he could. It was now time to explore new horizons and begin a journey which would further refine his craft. Vincent left The Netherlands to find the answers in Paris . . . . and in the company of the Impressionists.

New Beginnings: Paris

Vincent van Gogh had written to his brother, Theo, throughout early 1886 in an effort to convince Theo that Paris was where he belonged. Theo was all too aware of his brother's somewhat abrasive personality and resisted. As always, Vincent was undeterred and simply arrived in Paris unannounced in early March. Theo had no choice but to take Vincent in.

Van Gogh's Paris period is fascinating in terms of its role in transforming him as an artist. Unfortunately, Vincent's two years in Paris is also one of the least documented periods of his life--namely because biographers are so dependent on the letters between Vincent and Theo to supply the facts, and these letters stopped while the brothers lived together in Theo's apartment at 54 rue Lepic in Paris's Montmartre district.

Still, the importance of Vincent's time in Paris is clear. Theo, as an art dealer, had many contacts and Vincent would become familar with the ground-breaking artists in Paris at that time. Van Gogh's two years in Paris were spent visiting some of the early exhibitions of the Impressionists (displaying works by Degas, Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, Seurat and Sisley). There's no question that Van Gogh was influenced by the methods of the Impressionists, but he always remained faithful to his own unique style. Throughout the two years Van Gogh would incorporate some of the techniques of the Impressionists, but he never let their powerful influence overwhelm him.

Vincent enjoyed painting in the environs of Paris throughout 1886. His palette began to move away from the darker, traditional colours of his Dutch homeland and would incorporate the more vibrant hues of the Impressionists. To add further to the complex tapestry of Van Gogh's style, it was at this point in Paris that Vincent became interested in Japanese art. Japan had only recently opened its ports to outsiders after centuries of a cultural blockade and, as a result of this long-held isolationism, the western world was fascinated with all things Japanese. Van Gogh began to acquire a substantial collection of Japanese woodblock prints (now in the collection of the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam) and his paintings during this time (The Portrait of P re Tanguy, for example) would reflect both the vibrant use of colour favoured by the Impressionists, and distinct Japanese overtones. Although Van Gogh only ever produced three copies of Japanese paintings, the Japanese influence on his art would be evident in subtle form throughout the rest of his life.

1887 in Paris marked another year in which Vincent evolved as an artist, but it also took its toll on him, both emotionally and physically. Vincent's volatile personality put a strain on his relationship with Theo. When Vincent insisted on moving in with Theo, he did so with the hopes that they could better manage their expenses and that Vincent could more easily devote himself to his art. Unfortunately, living with his brother also resulted in a great deal of tension between the two. In addition, Paris itself was not without its temptations and much of Vincent's two years there was spent in unhealthy extremes: poor nutrition, and excessive drinking and smoking.

As was often the case throughout his life, poor weather during the winter months left Vincent irritable and depressed. Never was Vincent more happy then when he was outdoors communing with nature when the weather was at its finest. Whether painting or simply taking long walks, Vincent van Gogh lived for the sun. During the bleak winter months in Paris of 1887-88 Van Gogh became restless. And the same pattern was re-emerging. Van Gogh's two years in Paris had a tremendous impact on his ongoing evolution as an artist. But he had acquired what he was seeking and it was time to move on. Never truly happy in large cities, Vincent decided to leave Paris and follow the sun, and his destiny, south.

The Studio of the South

Vincent van Gogh moved to Arles in early 1888 propelled by a number of reasons. Weary of the frenetic energy of Paris and the long months of winter, Van Gogh sought the warm sun of Provence. Another motivation was Vincent's dream of establishing a kind of artists' commune in Arles where his comrades in Paris would seek refuge and where they would work together and support each other toward a common goal. Van Gogh took the train from Paris to Arles on 20 February 1888 heartened by his dreams for a prosperous future and amused by the passing landscape which he felt looked more and more Japanese the further south he travelled.

No doubt Van Gogh was disappointed with Arles during his first few weeks there. In search of the sun, Vincent found Arles unusually cold and dusted with snow. This must have been discouraging to Vincent who had left everyone he knew behind in order to seek warmth and restoration in the south. Still, the harsh weather was short lived and Vincent began to paint some of the best loved works of his career.

Once the temperature had risen, Vincent wasted no time in beginning his labours outdoors. Note the two complimentary works: the drawing Landscape with Path and Pollard Trees and the painting Path through a Field with Willows. The drawing was produced in March and the trees and landscape appear somewhat bleak after winter. The painting, however, executed a month later shows the very first spring buds on the trees. During this time Van Gogh painted a series of blossoming orchards. Vincent was pleased with his productivity and, like the orchards, felt renewed.

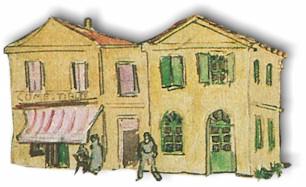

The months to follow would be happy ones. Vincent took a room at the Caf de la Gare at 10 Place Lamartine in early May and rented his famous "Yellow House" (2 Place Lamartine) as a studio and storage area. Vincent wouldn't actually move into the Yellow House until September, in preparation for establishing it as the base for his "Studio of the South."

The months to follow would be happy ones. Vincent took a room at the Caf de la Gare at 10 Place Lamartine in early May and rented his famous "Yellow House" (2 Place Lamartine) as a studio and storage area. Vincent wouldn't actually move into the Yellow House until September, in preparation for establishing it as the base for his "Studio of the South."

Vincent worked diligently throughout the spring and summer and began to send Theo shipments of his works. Van Gogh is often perceived today as an irritable and solitary figure. But he really did enjoy the company of people and did his best during these months to make friends--both for companionship and also to pose as much valued models. Although deeply lonely at times, Vincent did make friends with Paul-Eug ne Milliet and another Zouave soldier and painted their portraits. Vincent never lost hope in the prospect of establishing the artists' commune and began a campaign to encourage Paul Gauguin to join him in the south. The prospect appeared unlikely, however, because Gauguin's relocation would require even more financial assistance from Theo who had reached his limit.

In late July, however, Van Gogh's Uncle Vincent died and left a legacy to Theo. This financial influx would enable Theo to sponsor Gauguin's move to Arles. Theo was motivated both as a concerned brother and also as a business man. Theo felt that Vincent would be happier and more stable in the company of Gauguin and also Theo had hopes that the paintings he would receive from Gauguin, in exchange for his support, would turn a profit. Unlike Vincent, Paul Gauguin was beginning to see a small degree of success from his works.

Despite the improved state of Theo's financial affairs, Vincent nevertheless remained true to form and spent a disproportionate amount of his money on art supplies instead of the basic necessities of life. Malnourished and overworked, Van Gogh's health declined early October, but he was heartened upon receiving confirmation that Gauguin would join him in the south. Vincent worked hard to prepare the Yellow House in order to make Gauguin feel welcome. Gauguin arrived in Arles by train early on 23 October.

The next two months would be pivotal, and disastrous, for both Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin. Initially Van Gogh and Gauguin got on well together, painting on the outskirts of Arles, discussing their art and differing techniques. As the weeks passed, however, the weather deteriorated and the pair found themselves compelled to stay indoors more and more frequently. As always, Vincent's temperament (and most likely Gauguin's as well) fluctuated to match the weather. Forced to work indoors, Vincent's depression was assuaged, however, when he was encouraged and stimulated by a series of portraits he undertook. "I have made portraits of a whole family . . . ." he wrote to Theo (Letter 560). Those paintings, of the Roulin family, remain among his best loved works.

The relationship between Van Gogh and Gauguin deteriorated throughout December, however. Their heated arguments became more and more frequent--"electric" as Vincent would describe them. Relations between the pair declined in tandem with Vincent's state of mental health. On 23 December Vincent van Gogh, in an irrational fit of madness, mutilated the lower portion of his left ear. He severed the lobe with a razor, wrapped it in cloth and then took it to a brothel and presented it to one of the women there. Vincent then staggered back to the Yellow House where he collapsed. He was discovered by the police and hospitalized at the H tel-Dieu hospital in Arles. After sending a telegram to Theo, Gauguin left immediately for Paris, choosing not to visit Van Gogh in the hospital. Van Gogh and Gauguin would later correspond from time to time, but would never meet in person again.

During his time in the hospital, Vincent was under the care of Dr. Felix Rey (1867-1932). The week following the ear mutilation was critical for Van Gogh--both mentally and physically. He had suffered a great deal of blood loss and continued to suffer serious attacks in which he was incapacitated. Theo, who had rushed down from Paris, was sure that Vincent would die, but by the end of December and the early days of January, Vincent made a nearly full recovery.

The first weeks of 1889 would not be easy for Vincent van Gogh. After his recovery, Vincent returned to his Yellow House, but continued to visit Dr. Rey for examinations and to have his head dressings changed. Vincent was encouraged by his progress after the breakdown, but his money problems continued and he felt particularly depressed when his close friend, Joseph Roulin (1841-1903), decided to accept a better paying position and move with his family to Marseilles. Roulin had been a dear and faithful friend to Vincent for most of his time in Arles.

Vincent was quite productive in terms of his art throughout January and early February, producing some of his best known works such as La Berceuse and Sunflowers. On 7 February, however, Vincent suffered another attack in which he imagined himself being poisoned. Once again, Vincent was taken to the H tel-Dieu hospital for observation. Van Gogh was kept in the hospital for ten days, but returned once again to the Yellow House, provisionally: "I hope for good." (Letter 577)

By this time, however, some of the citizens of Arles had become alarmed by Vincent's behaviour and signed a petition detailing their concerns. The petition was submitted to the mayor of Arles and eventually to the superintendent of police who ordered Van Gogh readmitted to the H tel-Dieu hospital. Vincent remained in the hospital for the next six weeks, but was allowed to leave on supervised outings--in order to paint and to put his possessions into storage. It was a productive, but emotionally discouraging time for Van Gogh. As was the case a year before, Van Gogh returned to painting the blossoming orchards around Arles. But even as he was producing some of his best works, Vincent realized that his position was a precarious one and, after discussions with Theo, agreed to have himself voluntarily confined to the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole asylum in Saint-R my-de-Provence. Van Gogh left Arles on 8 May.

Confinement

Upon arrival at the asylum, Van Gogh was placed in the care of Dr. Th ophile Zacharie Auguste Peyron (1827-95). After examining Vincent and reviewing the case, Dr. Peyron was convinced that his patient was suffering from a type of epilepsy--a diagnosis that remains among the most likely possibilities, even today. The asylum was by no means a "snake pit," but Van Gogh was disheartened by the cries of the other residents and the bad food. He found it depressing that the patients had nothing to do all day--no stimulation of any kind. Part of Van Gogh's treatment included "hydro-therapy", a frequent immersion in a large tub of water. While this "therapy" was certainly not cruel in any way, neither was it in the least beneficial in terms of helping to restore Vincent's mental health.

As the weeks passed, Vincent's mental well-being remained stable and he was allowed to resume painting. The staff was encouraged by Van Gogh's progress (or, at least, at his not suffering any additional attacks) and in mid-June Van Gogh produced his best known work: Starry Night.

Van Gogh's relatively tranquil state of mind didn't last, however, and he was incapacitated by another attack in mid-July. During this attack Vincent tried to ingest his own paints and for that reason he was confined and not given access to his materials. Although he recovered fairly quickly from the incident, Van Gogh was discouraged at being deprived of the one thing that gave him pleasure and distraction: his art. After another week, Dr. Peyron relented and agreed to allow Van Gogh to resume his painting. His resumption of work coincided with an improved mental state. Vincent sent Theo letters detailing his precarious state of health; while at the same time Theo had similar issues to deal with. Theo's health had often been delicate and he had been ill throughout much of early 1889.

For two months Van Gogh was unable to leave his room and wrote to his sister: " . . . when I am in the fields I am overwhelmed by a feeling of loneliness to such a horrible extent that I shy away from going out . . . ." (Letter W14) In the weeks to follow, however, Vincent would again overcome his anxieties and resume working. During this time Vincent began to plan for his eventual departure from the asylum at Saint-R my. He expressed these thoughts to Theo who began to make inquiries of possible alternatives for Vincent's medical care--this time much closer to Paris.

Van Gogh's mental and physical health remained fairly stable throughout the remainder of 1889. Theo's health had recovered for the most part and, in the midst of preparing a home with his new wife, Theo was also assisting Octave Maus who was organizing an exhibition, Les XX, in Brussels in which six of Vincent's paintings would be displayed. Vincent seemed enthusiastic about the venture and remained quite productive throughout this time. The ongoing correspondence between Vincent and Theo worked out many of the details surrounding Vincent's showing within the exhibit.

On 23 December 1889, a year to the day after the ear slashing incident, Vincent suffered another attack: an "aberration" as he called it (Letter 620). The attack was serious and lasted about a week, but Vincent recovered reasonably quickly and resumed painting--this time mainly copies of other artists' works, due to being confined inside, both because of his mental health and also because of the weather. Sadly, Van Gogh suffered more attacks throughout the early months of 1890. These attacks came more frequently and left Vincent more incapacitated than any of those previously. Ironically, during this time when Van Gogh was probably at his lowest and most mentally despondent state, his works were finally beginning to receive critical acclaim. News of this, however, only served to depress Vincent further and renewed his hopes to leave the asylum and return to the north.

After making some inquiries, Theo felt that the best course of action would be for Vincent to return to Paris and then enter the care of Dr. Paul Gachet (1828-1909), a homeopathic therapist living in Auvers-sur-Oise, near Paris. Vincent agreed with Theo's plans and wrapped up his affairs in Saint-R my. On 16 May 1890 Vincent van Gogh left the asylum and took an overnight train to Paris.

"The sadness will last forever . . . . "

Vincent's journey to Paris was uneventful and he was met by Theo upon his arrival. Vincent remained with Theo, Theo's wife Johanna and their newborn son, Vincent Willem (named after Vincent) for three pleasant days. Never one to enjoy the hustle and bustle of city life, however, Vincent felt some stress returning and opted to leave Paris for the more quiet destination, Auvers-sur-Oise.

Vincent met with Dr. Gachet shortly after his arrival in Auvers. Although initially impressed by Gachet, Vincent would later express grave doubts about his competence, going so far as to comment that Gachet appeared to be "sicker than I am, I think, or shall we say just as much" (Letter 648). Despite his misgivings, however, Vincent managed to find himself a room in a small inn owned by Arthur Gustave Ravoux and immediately began painting the environs of Auvers-sur-Oise.

Over the course of the next two weeks, Van Gogh's opinion about Gachet softened somewhat and he became completely absorbed in his painting. Vincent was pleased with Auvers-sur-Oise, which afforded him the freedom denied him in Saint-R my, while at the same time provided him with ample subjects for his painting and drawing. Vincent's first weeks in Auvers passed pleasantly and uneventfully. On 8 June Theo, Jo and the baby came to Auvers to visit Vincent and Gachet and Vincent passed a very enjoyable day with his family. To all appearances, Vincent appeared quite restored--mentally and physically.

Throughout June, Vincent remained in good spirits and was remarkably productive, painting some of his best known works (Portrait of Doctor Gachet and The Church at Auvers, for example). The initial tranquility of the first month in Auvers was interrupted, however, when Vincent received news that his nephew was seriously ill. Theo had been going through a most difficult time throughout the previous few months: uncertainty about his own career and future, ongoing health problems and finally his own son's illness. Following the baby's recovery, Vincent decided to visit Theo and his family on 6 July and caught an early train. Very little is known about the visit, but Johanna, writing years later, would suggest that the day was strained and fairly tense. Vincent eventually felt overwhelmed and quickly returned to the more quiet sanctuary of Auvers.

During the next three weeks Vincent resumed his painting and, as his letters suggest, was reasonably happy. To his mother and sister Vincent wrote: "For the present I am feeling much calmer than last year, and really the restlessness in my head has greatly quieted down." (Letter 650) Vincent was absorbed in the fields and plains around Auvers and produced some brilliant landscapes throughout July. For Vincent life had appeared to settle into a productive and--if not happy--at least stable pattern.

Although details chronicled within the various reports conflict, the basic facts of 27 July 1890 remain clear. On that Sunday evening Vincent van Gogh set out, with his easel and painting materials, into the fields. There he took out a revolver and shot himself in the chest. Vincent managed to stagger back to the Ravoux Inn where he collapsed in bed and was then discovered by Ravoux. Dr. Mazery, the local practitioner, was called, as was Dr. Gachet. It was decided not to attempt to remove the bullet in Vincent's chest and Gachet wrote an urgent letter to Theo. Unfortunately, Dr. Gachet didn't have Theo's home address and had to write to him care of the gallery where he worked. This didn't cause a serious delay, however, and Theo arrived the next afternoon.

Vincent and Theo remained together for the last hours of Vincent's life. Theo was devoted to his brother, holding him and speaking with him in Dutch. Vincent seemed resigned to his fate and Theo later wrote: "He himself wanted to die; when I sat at his bedside and said that we would try to get him better and that we hoped that he would then be spared this kind of despair, he said 'La tristesse durera toujours' ('The sadness will last forever.') I understand what he wanted to say with those words." Theo, always his brother's greatest friend and supporter, was holding Vincent as he spoke his last words: "I wish I could pass away like this."

Vincent van Gogh died at 1:30 am. on 29 July 1890. The Catholic church of Auvers refused to allow Vincent's burial in its cemetery because Vincent had committed suicide. The nearby township of M ry, however, agreed to allow the burial and the funeral was held on 30 July. Vincent's long time friend, the painter Emile Bernard, wrote about the funeral in detail to Gustave-Albert Aurier:

|

The coffin was already closed. I arrived too late to see the man again who had left me four years ago so full of expectations of all kinds . . . .

On the walls of the room where his body was laid out all his last canvases were hung making a sort of halo for him and the brilliance of the genius that radiated from them made this death even more painful for us artists who were there. The coffin was covered with a simple white cloth and surrounded with masses of flowers, the sunflowers that he loved so much, yellow dahlias, yellow flowers everywhere. It was, you will remember, his favourite colour, the symbol of the light that he dreamed of being in people's hearts as well as in works of art. Near him also on the floor in front of his coffin were his easel, his folding stool and his brushes. Many people arrived, mainly artists, among whom I recognized Lucien Pissarro and Lauzet. I did not know the others, also some local people who had known him a little, seen him once or twice and who liked him because he was so good-hearted, so human . . . . There we were, completely silent all of us together around this coffin that held our friend. I looked at the studies; a very beautiful and sad one based on Delacroix's La vierge et J sus. Convicts walking in a circle surrounded by high prison walls, a canvas inspired by Dor of a terrifying ferocity and which is also symbolic of his end. Wasn't life like that for him, a high prison like this with such high walls--so high . . . and these people walking endlessly round the pit, weren't they the poor artists, the poor damned souls walking past under the whip of Destiny? . . . . At three o'clock his body was moved, friends of his carrying it to the hearse, a number of people in the company were in tears. Theodore Van ghogh [sic] who was devoted to his brother, who had always supported him in his struggle to support himself from his art was sobbing pitifully the whole time . . . . The sun was terribly hot outside. We climbed the hill outside Auvers talking about him, about the daring impulse he had given to art, of the great projects he was always thinking about, and about the good he had done to all of us. We reached the cemetery, a small new cemetery strewn with new tombstones. It is on the little hill above the fields that were ripe for harvest under the wide blue sky that he would still have loved . . . perhaps. Then he was lowered into the grave . . . . Anyone would have started crying at that moment . . . the day was too much made for him for one not to imagine that he was still alive and enjoying it . . . . Doctor Gachet (who is a great art lover and possesses on of the best collections of impressionist painting at the present day) wanted to say a few words of homage about Vincent and his life, but he too was weeping so much that he could only stammer a very confused farewell . . . (perhaps it was the most beautiful way of doing it). He gave a short description of Vincent's struggles and achievements, stating how sublime his goal was and how great an admiration he felt for him (though he had only known him a short while). He was, Gachet said, an honest man and a great artist, he had only two aims, humanity and art. It was art that he prized above everything and which will make his name live. Then we returned. Theodore Van ghog [sic] was broken with grief; everyone who attended was very moved, some going off into the open country while others went back to the station. Laval and I returned to Ravoux's house, and we talked about him . . . .1 |

Theo van Gogh died six months after Vincent. He was buried in Utrecht, but in 1914 Theo's wife, Johanna, such a dedicated and tireless supporter of Vincent's works, had Theo's body reburied in the Auvers cemetery next to Vincent. Jo requested that a sprig of ivy from Dr. Gachet's garden be planted among the grave stones. That same ivy carpets Vincent and Theo's grave site to this day.

1. Cahier Vincent 4: 'A Great Artist is Dead': Letters of Condolence on Vincent van Gogh's Death by Sjraar van Heugten and Fieke Pabst (eds.), (Waanders, 1992), pages 32-35.

References

![]() Return to main Van Gogh Gallery page

Return to main Van Gogh Gallery page