| |

| Author and art critic. His critiques were compiled and published in 1922 under the title 'Des Artistes'. |

Moreover, he ought not to be judged by the few paintings currently exhibited at the Pavillon de la Ville de Paris, despite the fact that they seem quite superior in intensity of vision, in richness of expression, and in power of style, to all those surrounding them. Certainly, I am not insensitive to the researches on light by M. Georges Seurat, whose seascapes, with their exquisite, profound luminosity, I like very much. I find a very lively electric atmosphere, the feminine grace, the bright elegance of M. van Rysselberghe. I am attracted to M. Denis’s small compositions, of so soft a tone, enveloped in such tender mysticism. I recognize, in M. Armand Guillaumin’s limited and unimaginative Realism a fine touch, as they say, of honest and sturdy technical qualities. And despite the blacks with which he unduly soils his figures, M. de Toulouse-Lautrec shows a real power, spiritual and tragic, in his study of physiognomies and penetrating character studies. M. Lucien Pissarro’s engravings have verve, sobriety, and distinction. Even M. Anquetin, amid obvious derivations, academic conventions, flawed eccentricities, caricatured uglinesses, at times offers us a nice glimpse of light—as in the Parisian horizon in the canvas titled Pont des Saint-Pères--and skillful harmonies of gray, as in one portrait of a woman. But none of these uncontestable artists—with whom one ought not confuse M. Signac, whose loud, dry, pretentious incompetence is irritating—captivate me as much as Vincent van Gogh. In his case I sense that I am in the presence of someone higher, more masterful, someone who disturbs me, moves me, and compels recognition.

It is perhaps not yet the time to tell the story of Vincent van Gogh as it ought to be told. His death is too recent, and it was too tragic. The memories I would evoke would revive the grief, which still brings tears. Therefore this study will be necessarily incomplete, for what was great and unexpected as well as too violent and excessive in the harsh yet delightful talent of Vincent van Gogh, is intimately bound up with the fatal mental illness that predestined him, still young, to death.

His life was quite disconcerting. At first he entered the art trade with his brother, who likewise met an early death, who ran the branch of Goupil’s on the boulevard Montmartre. He was a restless, tormented spirit, full of vague yet ardent inspirations, perpetually drawn to the summits where the human mysteries reveal themselves. No one knew then what stirred to him of the apostle or the artist; he himself didn’t know. He soon left the trade to study theology. He had, it seemed, a strong literary background and a natural tendency toward mysticism. These new studies seemed, for a time, to have given his soul the direction it craved. He preached. His voice echoed in the pulpits, among the crowds. But he soon suffered disillusionment. Before long, preaching seemed to him to be a vain thing. He did not feel close enough to the souls he wished to convert; his words blazing with love bounced off the walls of chapels and hearts without penetrating them. He thought that teaching would be more effective, and, forsaking preaching, he left for London, where he established himself as a primary-school teacher. For a few months, he taught the little children the ways of God.

Obviously, this all seems rather strange and disjointed; yet it is easily explained. The imperious artist within him, of which he was then still unaware, submerged itself in the apostle, lost itself in the evangelist, and wandered through dream-forests foreign and obscure to him. He felt that an invincible force was summoning him somewhere, but where? . . . that a light would illuminate somewhere at the end of his darkness, but when? There resulted a moral disequilibrium that drove him to the most incongruous actions, and the farthest from himself. It was upon his return from London that his vocation burst forth all of a sudden. He began to paint one day by chance. And it happened that, straight off, this first canvas was almost a masterpiece. It revealed an extraordinary painter’s instinct, marvelous and powerful qualities of vision, a keen sensibility that divined the living and restless form beneath the rigid appearance of things, and an eloquence and abundance of imagination that astounded his friends. Then Vincent van Gogh went to work in earnest. Work, without respite, work with all its obstinacies and all its raptures, seized hold of him. A need to produce, to create, took over the life, without stopping, without rest, as though he would make up for lost time. That lasted for seven years. And death came, tragically, to cut down his beautiful human flower. He left behind, the poor deceased, with all the hopes that such an artist could inspire, a considerable body of work, close to four hundred canvases and an enormous quality of drawings, of which many are absolute masterpieces.

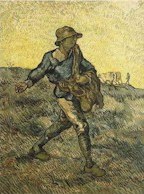

Van Gogh was of Dutch origin, from the homeland of Rembrandt, whom he seems to have greatly loved and admired. If one wished to cite an artistic lineage to this temperament of abundant originality, this ardor, this hyperaesthetic sensibility that was guided only by his personal impressions, one could perhaps say that Rembrandt would be his favored ancestor, the one in whom he most felt himself reborn. One rediscovers in his numerous drawings not resemblances [to Rembrandt] but a similar exasperated worship of the same forms and a parallel richness of linear invention. Van Gogh does not always adhere to the discipline nor to the sobriety of the Dutch master; but he often equals his eloquence and his prodigious ability to render life. Of Van Gogh’s unique artistic sensibility we have a very precise and quite valuable indication: namely, the copies that he executed after various paintings by Rembrandt, Delacroix, Millet. They are admirable. But they are not, strictly speaking, copies, these exuberant and imposing restitutions. They are, rather, interpretations through which the painter manages to recreate the work of others, to make them his own while preserving their original spirit and special character. In the Sower, by Millet but rendered with such superhuman beauty by Van Gogh, the movement is accentuated, the vision is broadened, the line is amplified to a symbolic significance. That which is Millet remains in the copy; but Vincent van Gogh has introduced something of his own through which the painting immediately takes on a look of a new grandeur. It is quite certain he brought to his observation of nature the same mental habits and superior creative gifts that he brought to these masterpieces of art. He could neither forget his personality nor contain it, whatever the spectacle or materialized dream before him. It overflowed from him in ardent inspirations over everything he saw, everything he touched, everything he felt. He was not, however, absorbed in nature; rather he had absorbed nature within himself: he forced it to become more supple, to mold itself to the forms of his thought, to follow him in his flights of fancy, to submit, even, to his characteristic distortions. To a rare degree, Van Gogh possessed that which distinguishes one man from another: style. In a crowd of paintings jumbled together, the eye, at a single glimpse, recognizes with certainty, those of Vincent van Gogh, just as it recognizes those of Corot, Manet, Degas, Monet, Monticelli, because they have a particular genius which cannot be otherwise, and which is style—that is, the affirmation of personality. And everything under the brush of this strange and powerful creator is animated by a strange life, independent of that of the things he paints, a life that is in him and that is him. He expends himself totally, on behalf of the trees, skies, flowers, and fields that he swells to capacity with the astonishing sap of his being. These forms multiply, run wild, writhe, extending even to the formidable madness of his skies where drunken celestial bodies spin and waver, where the stars stretch into disorderly rows of comets. Yet even in the upheaval of these fantastic flowers that rear up and tuft their feathers like demented birds, Van Gogh always maintains his wonderful qualities as a painter and a nobility that is moving, as well as a tragic grandeur that is terrifying. And, in the moments of calm, what serenity in the great sunlit plains, in the orchards in bloom, where the plum and the apple trees snow down joy, where the goodness of life radiates from the earth in flutters of light and expands into the tender paleness of peaceful skies and their refreshing breezes. Oh, how he understood the exquisite soul of flowers: How delicate becomes the hand that had carried such fierce torches into the dark firmament when it comes to bind these fragrant and fragile bouquets! And what caresses has he not found to express their inexpressible freshness and infinite grace?

Van Gogh was of Dutch origin, from the homeland of Rembrandt, whom he seems to have greatly loved and admired. If one wished to cite an artistic lineage to this temperament of abundant originality, this ardor, this hyperaesthetic sensibility that was guided only by his personal impressions, one could perhaps say that Rembrandt would be his favored ancestor, the one in whom he most felt himself reborn. One rediscovers in his numerous drawings not resemblances [to Rembrandt] but a similar exasperated worship of the same forms and a parallel richness of linear invention. Van Gogh does not always adhere to the discipline nor to the sobriety of the Dutch master; but he often equals his eloquence and his prodigious ability to render life. Of Van Gogh’s unique artistic sensibility we have a very precise and quite valuable indication: namely, the copies that he executed after various paintings by Rembrandt, Delacroix, Millet. They are admirable. But they are not, strictly speaking, copies, these exuberant and imposing restitutions. They are, rather, interpretations through which the painter manages to recreate the work of others, to make them his own while preserving their original spirit and special character. In the Sower, by Millet but rendered with such superhuman beauty by Van Gogh, the movement is accentuated, the vision is broadened, the line is amplified to a symbolic significance. That which is Millet remains in the copy; but Vincent van Gogh has introduced something of his own through which the painting immediately takes on a look of a new grandeur. It is quite certain he brought to his observation of nature the same mental habits and superior creative gifts that he brought to these masterpieces of art. He could neither forget his personality nor contain it, whatever the spectacle or materialized dream before him. It overflowed from him in ardent inspirations over everything he saw, everything he touched, everything he felt. He was not, however, absorbed in nature; rather he had absorbed nature within himself: he forced it to become more supple, to mold itself to the forms of his thought, to follow him in his flights of fancy, to submit, even, to his characteristic distortions. To a rare degree, Van Gogh possessed that which distinguishes one man from another: style. In a crowd of paintings jumbled together, the eye, at a single glimpse, recognizes with certainty, those of Vincent van Gogh, just as it recognizes those of Corot, Manet, Degas, Monet, Monticelli, because they have a particular genius which cannot be otherwise, and which is style—that is, the affirmation of personality. And everything under the brush of this strange and powerful creator is animated by a strange life, independent of that of the things he paints, a life that is in him and that is him. He expends himself totally, on behalf of the trees, skies, flowers, and fields that he swells to capacity with the astonishing sap of his being. These forms multiply, run wild, writhe, extending even to the formidable madness of his skies where drunken celestial bodies spin and waver, where the stars stretch into disorderly rows of comets. Yet even in the upheaval of these fantastic flowers that rear up and tuft their feathers like demented birds, Van Gogh always maintains his wonderful qualities as a painter and a nobility that is moving, as well as a tragic grandeur that is terrifying. And, in the moments of calm, what serenity in the great sunlit plains, in the orchards in bloom, where the plum and the apple trees snow down joy, where the goodness of life radiates from the earth in flutters of light and expands into the tender paleness of peaceful skies and their refreshing breezes. Oh, how he understood the exquisite soul of flowers: How delicate becomes the hand that had carried such fierce torches into the dark firmament when it comes to bind these fragrant and fragile bouquets! And what caresses has he not found to express their inexpressible freshness and infinite grace?

And how well he also understood the sadness, unknown and divine, in the eyes of the poor, mad, and sick that were his brethren!

Octave Mirbeau

Echo de Paris,

1 March 1891

Return to Van Gogh Archives page

Return to Van Gogh Archives page

Return to main Van Gogh Gallery page

Return to main Van Gogh Gallery page