Suzanne Chessler

Special to the Jewish News

One striking image, one painterly influence, one tutor and friend, one neighborhood and more than one dealer represent known Jewish connections to 19th-century painter Vincent van Gogh, whose powerful portraits will be exhibited Sunday, March 12-June 4 (2000) at the Detroit Institute of Arts.

Featuring 67 works from an international array of public and private collections, including pieces owned by the DIA, Van Gogh: Face to Face becomes the first display of this master's talent for capturing the bold and subtle expressiveness of the face.

The exhibit, a collaboration with the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and the Philadelphia Museum of Art, has been curated by specialists in 19th-century European and Dutch painting: George Keyes in Detroit, George T.M. Shackelford in Boston and Joseph Rishel in Philadelphia.

"What fascinates me much, much more than does anything else in my metier is the portrait, the modern portrait," Van Gogh has written. "I should like to do portraits which will appear as revelations to people in 100 years' time."

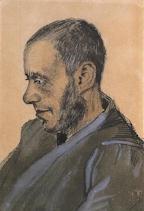

Done in pencil, pen, Chinese ink and watercolor, the 1882 rendering is on loan from a private collection in the Netherlands.

Although Van Gogh did many works without identifying the subjects, it is known that Blok is Jewish because of a letter written by the artist and presented on the Van Gogh Web site (http://www.vggallery.com) maintained by David Brooks, a Van Gogh enthusiast living in Canada. Brooks quotes the artist:

"And what's more, I have obtained yet another ornament for my studio. I got an amazing bargain of splendid woodcuts from The Graphic, in part printed . . . from the blocks themselves. Just what I've been looking for for years.

"Drawings by Herkomer, Frank Holl, Walker and others. I bought them from Blok the Jewish bookseller, and for five guilders picked the best from an enormous pile of Graphics and London News."

Without more than this sparse reference to his subject, Van Gogh's attitude toward the man--and Jews in general--could be ascertained by looking closely at the portrait itself.

Charles Dellheim, director of the humanities program at Arizona State University and an upcoming DIA speaker on Jewish art dealers as champions of modernism, suggests some questions for viewers of the now famous bookseller.

"The interesting question would have to do with how this Jewish person is depicted--positively or negatively," says Dellheim, who next year will be a fellow at the Center for Judaic Studies at the University of Pennsylvania.

"Is he depicted with a large nose or very fleshy lips or ears that point out? Those are some of the giveaways of antisemitic caricature."

"Israels was one of the leading painters of his generation in the Dutch Republic and was very much associated with the 19th-century French realist painting of the Barbizon School," curator Keyes explains.

"The Barbizon painters extolled the virtues of peasant life, thinking that the relationship of the peasant to the land was a self-evident, eternal truth, and Israels very much adopted the subject matter. He also represented scenes that encompassed the scale of human tragedy seen in the context of what it was like to be living the life of a peasant.

"There are strongly emotional scenes--for example, the death of a young mother or the death of a beloved husband or the death of a sailor at sea. These were all subjects he popularized, and Van Gogh, because of his strong sense of moral probity, was driven by a very strong evangelical streak and found those pictures tremendously appealing.

"When Van Gogh was in the small village of Nuenen, he did paint an enormous number of peasant subjects, and in representing these, he clearly was very deeply influenced by Jozef Israels.

"Israels relied heavily on earth tones, so that the whole palette is very subdued with a hushed, meditative and melancholy quality. Stylistically, when Van Gogh was in Holland, he also painted in these very subdued earth tones.

In more generic, academic terms, Van Gogh was influenced by his tutor, Dr. M.B. Mendes da Costa, a Jewish teacher in Amsterdam.

"Vincent devoted himself to studying (in anticipation of entering the clergy) from 1877 to 1878, and many of his studies were with Mendes da Costa, who taught Van Gogh Latin and algebra among other subjects," says Brooks, whose Web site provides Van Gogh letters describing the tutor and offers a picture of the man.

"Though they became good friends, Van Gogh found the studies to be too difficult (the Latin in particular), and he eventually ended them."

In the 1880s, as Van Gogh did portraits in The Hague, he was drawn to the areas where Jews predominantly lived and worked.

"There's no question that the quarters of The Hague that Van Gogh frequented, where he found many of these figures, were also very much the Jewish quarters of the city, so there's a very real connection there," curator Keyes says.

"There's a very interesting exhibition about Van Gogh at The Hague in which they talk about the part of the city or certain parts of the city, including the one that indeed had a large population of Jewish residents.

"An artist he admired very much throughout his life was [Dutch painter] Rembrandt, and we know that Rembrandt lived in the Jewish quarter of Amsterdam. Van Gogh must have known that fact and the fact that Rembrandt would search out these extraordinary characters as subjects for his paintings and etchings.

"No doubt unconsciously, Van Gogh must have been more or less thinking of doing the same thing in a parallel way during his own time."

B.J. Blackford, a retired educator living in Birmingham, is a distant relative of Van Gogh and has done considerable research about the painter.

Blackford, who lectures about the man and his work, is familiar with one drawing he did in the Jewish quarter of The Hague, known as Paddemoes.

"It's a street scene with two or three people walking," says Blackford, who quotes a passage written by Van Gogh:

"If you look at the history of Van Gogh's reception, the role played by Paul Cassirer, a Berlin art dealer from a very eminent German Jewish family, is very striking," Dellheim explains. "To a lesser extent, Parisian dealers, the Bernhein brothers, have some very close connections.

"Anybody who hears my talk will have a better sense not only of the role of Jewish art dealers in the marketing of Van Gogh's works, but the works of a whole variety of other modern artists.

"In the 19th century, most Jews were virtual strangers to the culture of the west, especially its visual culture. Yet by the early 20th century, if you went down the major street for selling art in Paris, Rue La Boetie, you would find a host of Jewish art dealers. It's fascinating how and why this happens, and it tells a lot about Jewish culture.

"With the post-Impressionists like Van Gogh, Jews are beginning to make themselves felt as historians, critics, dealers, connoisseurs and painters, too."

One such revelation, more than 100 years later, is Portrait of the Bookseller, Blok, which seems to be the artist's only work in this exhibit known to show a member of the Jewish community, in this case from The Hague.

One such revelation, more than 100 years later, is Portrait of the Bookseller, Blok, which seems to be the artist's only work in this exhibit known to show a member of the Jewish community, in this case from The Hague.

A group of portraits in the collection, including Beardless Fisherman Wearing a Sou'wester and Fisherman with a Sou'wester, are not known as portraying Jewish subjects, but are the results of Van Gogh's esteem for Jewish painter Jozef Israels.

Van Gogh did paintings with subjects referred to as "orphan men," who were basically living in a city-funded almshouse at The Hague and are seen in Face to Face. Their weathered visages show a parallel to Israels' images.

A group of portraits in the collection, including Beardless Fisherman Wearing a Sou'wester and Fisherman with a Sou'wester, are not known as portraying Jewish subjects, but are the results of Van Gogh's esteem for Jewish painter Jozef Israels.

Van Gogh did paintings with subjects referred to as "orphan men," who were basically living in a city-funded almshouse at The Hague and are seen in Face to Face. Their weathered visages show a parallel to Israels' images.

"Van Gogh ranked Israels extremely highly in terms of the artists he particularly admired. There's a wonderful letter where he talks about the ideal gallery, and at [one] end it would have a large painting by Jozef Israels. The painting, Old Friends, is now in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. It presents a very ancient peasant seated at a table with a dog (staying close)."

"Van Gogh ranked Israels extremely highly in terms of the artists he particularly admired. There's a wonderful letter where he talks about the ideal gallery, and at [one] end it would have a large painting by Jozef Israels. The painting, Old Friends, is now in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. It presents a very ancient peasant seated at a table with a dog (staying close)."

Drawn To Jewish Quarters

"I did not say anything until we came to a little drawing which I once sketched at 12:00 at night while strolling around with Breitner. [It was of] the Paddemoes [the Jewish quarter near the new church] as seen from the peat market. Next morning, I had worked on it again with my pen."

When Dellheim gives his talk on May 17, he will explore the marketing of Van Gogh's works by Jewish art dealers.

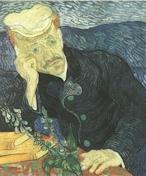

"Van Gogh's art, especially its posthumous history, intersects with the history of modern Jews in Europe and America," Dellheim says. "There were many collectors and dealers who were interested in Van Gogh and who were important in buying and popularizing his work. The very famous portrait of Dr. Gachet had a number of Jewish owners.

"Van Gogh's art, especially its posthumous history, intersects with the history of modern Jews in Europe and America," Dellheim says. "There were many collectors and dealers who were interested in Van Gogh and who were important in buying and popularizing his work. The very famous portrait of Dr. Gachet had a number of Jewish owners.

This article has been reproduced with the kind permission of

The Detroit Jewish News.

Return to main Van Gogh Gallery page

Return to main Van Gogh Gallery page