![]()

My Appreciation of Van Gogh

By Lewis McLeod

What initially impressed/attracted me to the work of Van Gogh were the following:

We all know--or should do eventually, that Life is many things or a "many splendoured thing! Its food getting, seeking shelter, or your own place and space. It's playing, fighting, hoping, aspiring and sorrowing. But the centre--the core of your life, is the process of getting ourselves believed-in, appreciated and accepted by your peers or your own generation.

This was also the case of Vincent Van Gogh--just like us.

But according to research, he was NOT successful in making his personality effective in his particular environment with his fellow human beings. We have all read of the 122 year old woman of Arles, Jeanne Calment, who met him and recalled he "was very ugly, ungracious, impolite, sick--I forgive him, they called him loco". Remember also, when he was released from the hospital-asylum, his neighbours feared him. In fact they got up a petition that he remain confined or leave Arles. The local police barred him from his yellow house. Eventually he is readmitted to the asylum where he is "shut up in a cell all the livelong day" without his pipe, books or paints. The public everywhere is notoriously fickle in memory, attitude or understanding. Even today's generation, despite advances in education or the internet don't realise that personality and talent are two separate aspects of character, not necessarily complimentary. He asked to be called "Vincent" and signed his paintings as such, because the French couldn't pronounce his family name. That's not really new! Even educated Americans today don't take the trouble to pronounce the name of the painting genius they claim to love. They pronounce "Gogh" as "goe" instead of "ogh" as in Scottish "Loch".

What is heroic about "our" Vincent is that despite all this cruel loneliness, and his depression, our then unknown artist Vincent believed in himself. As we now know, he studied, learned, practiced hard all the techniques of painting in his time. Then having assimilated all that is best that- he admired--in the work of his favourite artists--Ando Hiroshige, Millet, Daumier, Delacroix, Sisly, Seurat, Signac, Lautrec, Pissarro, Gauguin, and not least--Monticelli, each for different things, he set about painting in his own individual style. Thick textural, almost thatched, sculpted, brush strokes with magnificent colour stimuli and harmony.

It's difficult for young people today to appreciate, but he was the first to paint the sun directly in his pictures. Also he actually went out at night (allegedly with candles on the brim of his hat and on his easel!) and painted "The Cafe Terrace at Night" (No. 1580). See his moon and stars in "the Starry Night" (No. 1731). In 1887-89 this was revolutionary expressionism in Art. But in the wide Art world of his day, his work was unseen and unknown.

First, there was obviously his profound love of nature and his uncompromising sense of social reality. Always in his work there is structure, a feeling of growth, whether in a plant or a facial portrait. He clearly had his own developed self trained sense of colour. He appreciated and knew Delacroix's theories of colour, nature's tonal harmony. He sensed the effects of colour contrast and their stimuli to the onlooker's brain; long before and without the proof of today's neuroscience. Then, there are the totally individualised and unique, purposeful--very definite brush strokes. As with his pen and ink dots and line sketches, he knew how to use a full brush of colour and make it "sit" with a single stroke that fitted in and enhanced the whole ambient effect. A good example of this, for me, is his painting of Marguerite Gachet in her totally white dress playing the piano. (No. 2048) It's not totally white--only the overall effect. Look closely, its hundreds of similar sized, definite brush strokes of white, cream, pale grey-blue, pink, and sepia with added "sculptured" separation lines of her jacket and dress, most likely done by the pointed handle end of his brush. Or by his Japanese bamboo reed "pen". No flat toned white with gray shaded folds for him.

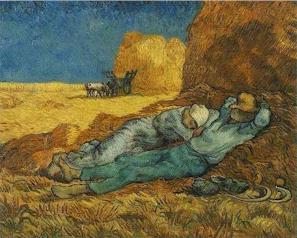

What is so endearing about Vincent is that he must have instinctively known that the golden rule of Art is that there is no golden rule. So being very much himself, he unashamedly learned by copying the work of those artists he personally admired. He took from each, that detail of technique, style, mannerism that he admired and achieved the effect he likewise wanted in his work. See the many copies of Millet (Millet's original shown at right), specially his "Noon-day Rest" (No. 1881) and how he only took the theme, but made the painting his very own, so different. The composition, the details of these two peasants resting in the shade of the midday sun are exactly copied. But instead of that academic naturalism of the day, he gives the scene the feeling of the hot southern sun, the texture of the corn, the colour harmony of blue yellow and gold.

Notice he called these copy works "translations". For the VG student you can see the early influence of his graphic lined figures or objects he saw & took from the Japanese, from Seurat and others. But which he abandoned later, for his own longer preferred brush strokes. Then having assimilated all that he loved in the work of others, he finally took and developed the Monticelli thick impasto technique, which he perfected and made his own, through sculpting the thick paint. You see this in all his breezy Cypress trees (No. 1748) and in "The Starry Night" and other paintings. What a wonderful way to express movement of the wind in the tress and rolling clouds, with thick swirling energetic vibrant brush strokes.(see "Wheatfield with Cypress Trees-1889" (No. 1756)

All this nonsense of critics then, and now about the madman with a cut off ear, furiously painting in some epileptic fit is totally unfair to his character, his learning, his outlook on life. All his pictures are composed. There is nothing random about his work. He knew what he was doing. That's why he used a "perspective frame". See his drawing of one that he used. He also knew that Life and Nature are irregular, (from Darwin) that it has tremendous variety. None of his painted fields, floors, plants, faces have one flat tone or colour, at least not after he studied and worked with the Impressionists. Even that short period with Gauguin who persuaded him to try contrasting large spatial backgrounds with flat tones of colour and boldly outlining them. He still varied the subtlety within these flat tonal harmonies. (Study his "L'Arlesienne, Mme. Marie Ginoux" No. 1624) as a sample of this.

Van Gogh was mainly a self-trained artist, despite initial lessons from Mauve or the few months at the Paris Corman studio. He learned about perspective. But in his painting of his "bedroom in Arles" No. 1771 or 1793 he ignores true perspective. It was as if he was looking at the room with a very wide angle contact lens. There is an oddity about the room, everything seems to come towards you. Somehow these yellow chairs feel as if they are about to slide towards the bottom frame. Also, note there are no shadows in this painting. These conscious factors make the picture arresting, strangely unusual. He wanted to make a personal visual statement. The feeling as he said of "absolute restfulness". Like his early Japanese print studies he thinks that colour can be therapeutic. Here "colour was to do everything".

Though fascinated with Line, shape, form, colour, harmony, contrasts and their spatial relationships; as an artist, he kept philosophically grounded in reality or in nature's truth. Remember, his really close friends like Pere Tanguy and Joseph Roulin often discussed Socialism. They had read Zola and Balzac like himself, so they knew the social realities of their times. So a flower is a flower, a chair a chair, and old pair of boots is precisely that. But through his artistry his flowers, chairs and boots have his charismatic combinations of colour. To use words precisely, he was what is called -- dialectical. He creates order out of disorder. He understood conflict, opposing colours, their interaction and interpenetration of lines and planes within the frame. He discovered what artists today don't seem to know. How to contrast the three primary colours blue-red-yellow with the mixture of the other two!! So you see how his paintings can shimmer, increase one another's intensity of colour, or can neutralise themselves to a dull grey when mixed. Vincent was a passionate man with strongly held opinions. He hated the works/subjects of the Academic Salons. They believed brilliant colours cannot be as beautiful as subdued refined tones of colour. Vincent said "The Dutch painters lack courage. They don't dare to use genuine colours on their canvas". Vincent expresses his temperament, the ambience of feeling. So he has green skies, blood-red trees or purple fields ("Wheat stacks with Reaper" -- No. 1482). In his two paintings called the "Sower" he reverses the normal to express sunset. The sky is stippled chrome yellow, the sun as bright as a new fried egg and the fields bluish violet. The field seems to shimmer near the corn. That is the wonder of Vincent. He teaches you to see---really observe. If you have studied,- not glanced at his pictures, you too will "see" somewhere-sometime scenes, objects or portraits in a given quality of light that will give you that vision, perspective, dimension and memory that he had in abundance. Vincent sharpened the harmony of colours, yet preserving their objective integrity. He constantly strove to give from nature his inner creative self and temperament. See his "Trees in front of the Asylum" at Saint Rémy (No. 1799) (Armand Hammer Foundation--Los Angeles) or "Ravine" (Museum of Fine Arts--Boston) or "undergrowth with Two Figures" (Cincinnati Art Museum).

So Vincent the tri-linguist, man of letters, read the great books of his day, disciplined in his time schedule, would paint energetically, furiously getting all these detailed brush strokes in place. His visual energy force would convey his feelings from his intense gaze, down his arm to his handheld brush, placing, stroking the brush to the final colour placement as he saw it. Without doubt he had that rare decorative vision. By that I mean his work is positive, visually leisurely, relaxing. Who does not admire his Irises? (No. 1691. Paul Getty Centre. LA) You can live with his paintings. They have feelings because they are intensely expressive. There is love in his paintings. In some of his paintings his choice of colours and their contrasting harmony with others are just astounding. They are mostly textural, translucent even iridescent and alive. As Emile Zola perceptively observed, "A work of Art is a corner of creation seen through a temperament". A corner of creation--that is a memorable phrase. This is precisely where he painted his famous "Irises" in the corner of the asylum's garden. Because of his illness, his freedom of movement was restricted. "Irises" somehow does express restriction, being closed in. He observes nature's reality, but it's his metaphorical reality. The picture frame is tightly closed. All the irises are gorgeously colourfully blooming. But there--in their midst to the side--is a lonely white iris that stands alone. Was this for real before him, within his perspective frame? Or is it a personal symbol of his own lonely self, trying to survive and stand out. We will never know and it doesn't really matter. Its a recognised world masterpiece we all love. So much so, that it fetched at a New York auction in 1987, a century later, the sale price of 49 million pounds!

No other artist has had so many articles, books, films/videos about him. His honesty and sincerity, intense passion and genius in paint have given him a deserved place in history. Sadly there has been a lot of nonsense, religious and Freudian claptrap attributed to him. Hundreds of learned psychiatrists, neuroscientists have written their opinions on his illness -epilepsy, brain seizures, bouts of depression. Schizophrenia and dipsomania are the presumed causes of his illness. OK, it's interesting with the hindsight of modern medicine and brain surgery to read the views of today's expert medics. But most of it is speculation and conjecture. Does it help us to enjoy his work? His whole life's history, short as it was, from religious rejection (and hypocrisy), family feuds, romantic refusals are aspects of life, that even today happen to people. Its his total never failing honesty and sincerity of view, his undying love of nature and for the simple folk he met that captivates the world. Vincent reminds me a little of Ben Traven, novelist, great short story writer (1882-1969). He wrote "Treasure of Sierra Madre". He courted anonymity. His true identity was only revealed in 1979. He said "if you want to know me--read my books"

All that interests me in Vincent's letters are the remarks he makes about his love of painting. For example, he said "It's true I turn my back completely on nature, when I transform a sketch into a painting, decide upon the colours, enlarge or simplify, but in relation to the actual form I am afraid of moving too far away from reality and thus of not being exact enough. I don't in fact invent the whole painting, on the contrary, I discover the thing, but it must come out of nature". So in this way he keeps the respect for the subject. Likewise, he said of the art of portrait painting it "lets me develop that which is best and deepest within me". Clearly these are not the words of some religious simpleton. Our Vincent had very definite views and opinions shaped from his past peers and own experiences of keen observation. Primarily, I judge him on his work which is what he would have wished I'm sure. I know what it's like to live in a Calvinist country or community. My birth country had traditionally these same stupid moral values, males mustn't cry or carry flowers or push a pram, women are only for babies and the home and obedient to the male, as master. I couldn't kick a ball on the Sabbath as a child and had go to Sunday school. At Art school I was reasonably good at watercolours but the Art teacher insisted I paint in gouache because it was her forte. I also hated painting beheaded half casts of classical human torsos. So I easily empathise with Vincent. Its his incredible joy to see paintings that lift my soul, not his miserable frustrations and conceptions of his early life.

Then, I saw an artist who painted the sun--which was behind a farmer; sowing seeds as he walked past a purple shaded silhouetted tree. You couldn't see his face, but the whole ambient light suggested to me this man had a long tiring day and was still not finished. It was "The Sower" by Vincent. It was the first time I realised how to fill, space, arrange content in a pleasing and arresting pictorial composition. It was to be another 30 years before I discovered the full works of Van Gogh.

But filling a frame, be it square, rectangular or circular is in itself a craft, a skill. Again Vincent learned this and became a master. He made his compositions so casual, and naturally obvious, you were not aware they were "composed" in the first place. From Lautrec he learned how to create the feeling of movement by linear diagonals conflicting with the vertical sides of the frame. He learned from Rembrandt how to use side and back light for pronounced modelling and to get the third dimension of depth and space. But his originality was truly understanding colour stimuli--even pure colour and their complimentary tones and hues. In his maturity, but still always experimenting, his speciality has to be his full loaded impasto brushstrokes that he used to convey texture and movement in cornfields, tree-branches or for facial portraits such as Patience the Gardener, (No. 1548) Roulin the Postman, his wife, Dr. Gachet and his self-portraits.

Vincent, the poor unknown genius of paint becomes voted today the most popular painter in the world, whose paintings today sell for more than even Picasso and Monet.

Very few people speak about Vincent's own ideal wish in life. What was it?

To found a co-operative artists' community of colourists. A commune which would eliminate all material needs and where everyone could enjoy colourful decorative picture paintings freely. I wish there were records of his discussions with Pere Tanguy and Roulin the Postman about these ideals he had.

I recently discovered 15 of Vincent's paintings I never even knew existed. One of my favourites is in the Hermitage museum in Russia. Most are in private collections. Now I can see them on my computer screen. Well today, a century later, we can at least see a fair quality representation of Vincent Van Gogh's work on the world-internet on this very excellent website. Vincent would have loved the internet and this website just for that reason.

At last, his wished for ideal, a net world community of his Art----for free!

I hope you too can enjoy it. My best wishes,

Lewis McLeod

March 2001

Return to Visitor Submissions page

Return to Visitor Submissions page

Return to main Van Gogh Gallery page

Return to main Van Gogh Gallery page