![]()

Emile Zola's Influence Upon Vincent van Gogh

By Jared Dockery ©

Introduction

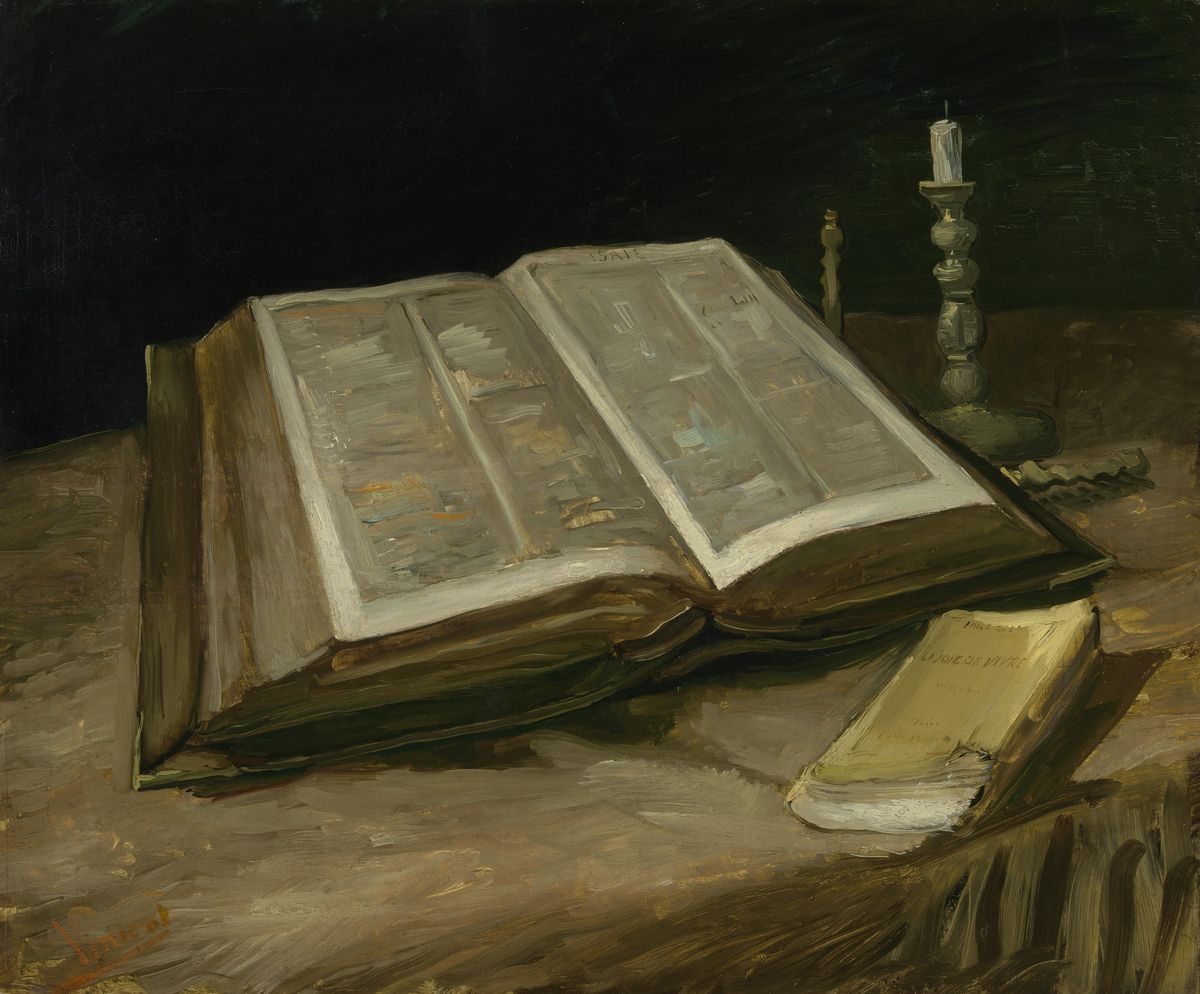

When van Gogh painted this in

1885, it had been several years since his disappointing failure to receive continued

missionary funding in late 1879 and his subsequent turn to painting. Van Gogh had

subsequently clashed with his father over religious views and this painting followed soon

after his father's death (and may even have depicted his father's very Bible).

It has been suggested that the painting represented van Gogh's shift away from his

father's ancient religion embodied in the Bible, to modernity embodied in Zola's

writing. One 1990 critique of the painting argued that van Gogh "felt free to

criticize his father by clearly contrasting the Bible, which stands for the latter's

traditional faith, with Zola's La Joie de Vivre."8 While not specifically

referring to Still-life with Open Bible, André Krauss has argued, "with time, Van

Gogh left behind his religious zeal, but he continued more and more to relate the world of

literature to real life, and eventually he declared that art, literature and life were in

fact but one."9

One problem with this

interpretation is that the Bible in Still-life with Open Bible dominates the entire

picture, while the novel, although it is pictured in front, is tiny in comparison. It

might be argued that this merely reflects the proper physical sizes of the two books; or

alternately, that van Gogh believed the Bible possessed a deeper influence over the minds

of men in 1885 than did modern literature. But if the respective sizes of the two books

can be dismissed, why does van Gogh portray the Bible as being open and Zola's novel

as being shut?

Kathleen Erickson is persuasive

when she argues that van Gogh was merely trying to synthesize (not replace) religion with

modernity. "He rejected the Church, thereafter referring to the inside of a church as

the white-washed wall of icy hypocrites," she writes. "But he did not reject

Christianity, seeking rather to find a synthesis of his faith with modernity. This was

particularly apparent in his love of modern literature, especially the ironic Realism of

Zola and the Romantic tragedies of Hugo. Van Gogh was especially drawn to the Christ-like

heroes, such as Pauline in Zola's La Joie de Vivre and Jean Valjean in Hugo's

Les Miserables."10

While Cliff Edwards is more

inclined to believe that van Gogh turned his back on the Bible than Erickson is, both

authors point to a similarity between the two books pictured in Still-life with Open

Bible. The Bible is opened to Isaiah 53, the messianic Psalm of the Suffering Servant:

When van Gogh painted this in

1885, it had been several years since his disappointing failure to receive continued

missionary funding in late 1879 and his subsequent turn to painting. Van Gogh had

subsequently clashed with his father over religious views and this painting followed soon

after his father's death (and may even have depicted his father's very Bible).

It has been suggested that the painting represented van Gogh's shift away from his

father's ancient religion embodied in the Bible, to modernity embodied in Zola's

writing. One 1990 critique of the painting argued that van Gogh "felt free to

criticize his father by clearly contrasting the Bible, which stands for the latter's

traditional faith, with Zola's La Joie de Vivre."8 While not specifically

referring to Still-life with Open Bible, André Krauss has argued, "with time, Van

Gogh left behind his religious zeal, but he continued more and more to relate the world of

literature to real life, and eventually he declared that art, literature and life were in

fact but one."9

One problem with this

interpretation is that the Bible in Still-life with Open Bible dominates the entire

picture, while the novel, although it is pictured in front, is tiny in comparison. It

might be argued that this merely reflects the proper physical sizes of the two books; or

alternately, that van Gogh believed the Bible possessed a deeper influence over the minds

of men in 1885 than did modern literature. But if the respective sizes of the two books

can be dismissed, why does van Gogh portray the Bible as being open and Zola's novel

as being shut?

Kathleen Erickson is persuasive

when she argues that van Gogh was merely trying to synthesize (not replace) religion with

modernity. "He rejected the Church, thereafter referring to the inside of a church as

the white-washed wall of icy hypocrites," she writes. "But he did not reject

Christianity, seeking rather to find a synthesis of his faith with modernity. This was

particularly apparent in his love of modern literature, especially the ironic Realism of

Zola and the Romantic tragedies of Hugo. Van Gogh was especially drawn to the Christ-like

heroes, such as Pauline in Zola's La Joie de Vivre and Jean Valjean in Hugo's

Les Miserables."10

While Cliff Edwards is more

inclined to believe that van Gogh turned his back on the Bible than Erickson is, both

authors point to a similarity between the two books pictured in Still-life with Open

Bible. The Bible is opened to Isaiah 53, the messianic Psalm of the Suffering Servant:

He is despised and rejected of men; a man of sorrows, and acquainted with grief: and we hid as it were our faces from him; he was despised, and we esteemed him not. Surely he hath borne our griefs, and carried our sorrows: yet we did esteem him stricken, smitten of God, and afflicted. But he was wounded for our transgressions, he was bruised for our iniquities: the chastisement of our peace was upon him; and with his stripes we are healed.11 Meanwhile, one of the main character's in Zola's deceptively titled La Joie de Vivre (The Joy of Life) is Pauline Quenu, an orphan who forsakes her own pleasures to care for others. Rather than a contrast between old religion and modernism, van Gogh actually saw a thread connecting the two the attractiveness of a life lived for others.12 Two years after painting Still-life with Open Bible, van Gogh wrote a letter to his sister Wilhelmina which touched on the theme of literature as supplement to the Bible. "The work of the French naturalists, Zola, Flaubert, Guy de Maupassant, de Goncourt is magnificent. Is the Bible enough for us?" he wrote. "In these days, I believe Jesus himself would say to those who sit down in a state of melancholy, It is not here, get up and go forth. Why do you seek the living among the dead?" He continued, "If the spoken or written word is to remain the light of the world, then it is our right and our duty to acknowledge that we are living in a period when it should be spoken and written in such a way that in order to find something equally great, and equally good, and equally original, and equally powerful to revolutionize the whole of society we may compare it with a clear conscience to the old revolution of the Christians."13 Edwards sees this as proof that "Vincent had now left the Bible to the past, and turned his attention to the only Bible applicable to his own day, those new things' that revolutionize the present." But van Gogh had not claimed the Bible contained no truth; rather he claimed that it could no longer properly communicate that truth to a modern world. In fact, he remained fond of the Bible; in the same letter he wrote, "I myself am always glad that I have read the Bible more thoroughly than many people nowadays, because it eases my mind somewhat to know that there were once such lofty ideas."14 Van Gogh's retention of spiritual instincts is obvious in his continued veneration of Jesus of Nazareth, demonstrated by a letter he wrote to his brother on June 23, 1888 long after he had supposedly turned his back on religion. "Christ alone, of all the philosophers, Magi, etc. has affirmed, as a principal certainty, eternal life, the infinity of time, the nothingness of death, the necessity and the raison d'etre of serenity and devotion," van Gogh wrote. "He lived serenely, as a greater artist than all other artists, despising marble and clay as well as color, working in living flesh. That is to say, this matchless artist, hardly to be conceived of by the obtuse instrument of our modern, nervous, stupefied brains, made neither statues nor pictures nor books; he loudly proclaimed that he made living men, immortals."15 If Zola did not influence van Gogh to jettison his spiritual and religious instincts, what was the author's influence upon the painter? "So ardent an admirer of Zola" Zola never seems to have been far from van Gogh's mind because his correspondence is sprinkled with references to the novelist. In July 1882 (three years before Still-life with Open Bible) van Gogh admonished Theo to "read as much of Zola as you can; that is good for one, and makes things clear."16 In early 1884, he told his brother of an article which Zola had recently written referring to Manet as the painter who had ushered in the modern age (although he disagreed with Zola and believed that the "essentially modern painter who opened a new horizon to many" was instead Millet).17 Writing from Arles, France in May 1888 he informed his brother, "I have just re-read Au Bonheur des Dames, by Zola, and it seems to me more beautiful than ever."18 Several weeks later, he declared that "you feel Zola and Voltaire everywhere involuntarily" in Arles.19 In the last year of his life, the tortured artist referred to himself as "being so ardent an admirer of Zola and de Goncourt."20 In light of van Gogh's constant references to Zola, we may deduce that the novelist did indeed influence the painter. First, van Gogh would have found in Zola's writings reinforcement of his own social conscience. Van Gogh's credentials as sympathizer to the poor were impeccable. His own religious upbringing, with its emphasis upon Christ-like service to others, would have been sufficient to instill in him a concern for the poor; when he shared the miseries of poor Belgium coal-miners in 1879, this would have only been strengthened.21 When van Gogh turned away from organized religion to painting, he retained a concern for the poor. "He stated this view [that art had a clearly defined social function] repeatedly in his letters," writes Krauss. "According to him, the poor people of the working classes were not only the proper subject of art, but should also have been the recipients of such an art. He thought that art would console and edify them. In that sense he conceived of art as a mission, and through his artistic creativity he fulfilled his own moral obligation to society and the times he lived in."22 In 1885, the same year he painted Still-life with Open Bible, van Gogh also painted The Potato Eaters. Erickson not only refers to this as the most important work of van Gogh's Dutch period, but also writes that "many consider [it] to be the first truly realistic peasant painting in western art."23 The painting, which depicts a humble coal-mining family sitting down to a meal of potatoes and coffee, is reminiscent of Zola's Germinal, which appeared just before. Van Gogh later mentioned the novel during the summer of 1888: "We have read La Terre and Germinal," he wrote, "and if we are painting a peasant we want to show what we have read has come in the end to very near being part of us."24 It would be too much to claim that van Gogh received his social conscience from Zola, but it is not too much to claim that the views of the latter reinforced those of the former. The Potato Eaters, 1885

Second, van Gogh apparently drew

artistic inspiration from Zola. The novelist is representative of the Realist movement in

France, which Krauss argues "was the movement that closest resembled Van Gogh's

theories on the social function of art."25 But van Gogh himself pointed out that Zola

was not completely a realist. In a letter to Theo written some time in the fall of 1885,

van Gogh writes: "Romance and romanticism are of our time, and painters must have

imagination and sentiment. Fortunately realism and naturalism are not free from it. Zola

creates, but does not hold up a mirror to things, he creates wonderfully, but creates,

poetizes, that is why it is so beautiful. So much for naturalism and realism, which are

still connected with romanticism."26 While van Gogh painted peasants, cornfields and

starry skies, he did not hold up a mirror to such things; rather, he too poetized them.

Third, van Gogh drew solace from

Zola's understanding of the misunderstood artist. "What touches me most deeply

in Zola's L'oeuvre is the figure of Bongrand Jundt," he wrote in 1888.

"What he says is so true. You think, you pour souls, that when an artist has

established his talent and his reputation he is safe. On the contrary, it is now denied

him henceforth to produce anything which is not absolute. His reputation itself forces him

to take more pains over his work, as the chances of selling grow fewer. At the least sign

of weakness the whole jealous pack will fall on him and destroy that very reputation and

the faith that the changeable and faithless public has momentarily had in him.'"27

Finally, van Gogh on one

occasion used Zola to justify his personal life to his brother. Some time during the

winter of 1881-82, van Gogh took a pregnant prostitute whom he called Sien into his

lodgings in the Hague and cared for her. Van Gogh's family, not surprisingly,

disapproved. It was to Zola that he turned for his defense in a letter to Theo.

Second, van Gogh apparently drew

artistic inspiration from Zola. The novelist is representative of the Realist movement in

France, which Krauss argues "was the movement that closest resembled Van Gogh's

theories on the social function of art."25 But van Gogh himself pointed out that Zola

was not completely a realist. In a letter to Theo written some time in the fall of 1885,

van Gogh writes: "Romance and romanticism are of our time, and painters must have

imagination and sentiment. Fortunately realism and naturalism are not free from it. Zola

creates, but does not hold up a mirror to things, he creates wonderfully, but creates,

poetizes, that is why it is so beautiful. So much for naturalism and realism, which are

still connected with romanticism."26 While van Gogh painted peasants, cornfields and

starry skies, he did not hold up a mirror to such things; rather, he too poetized them.

Third, van Gogh drew solace from

Zola's understanding of the misunderstood artist. "What touches me most deeply

in Zola's L'oeuvre is the figure of Bongrand Jundt," he wrote in 1888.

"What he says is so true. You think, you pour souls, that when an artist has

established his talent and his reputation he is safe. On the contrary, it is now denied

him henceforth to produce anything which is not absolute. His reputation itself forces him

to take more pains over his work, as the chances of selling grow fewer. At the least sign

of weakness the whole jealous pack will fall on him and destroy that very reputation and

the faith that the changeable and faithless public has momentarily had in him.'"27

Finally, van Gogh on one

occasion used Zola to justify his personal life to his brother. Some time during the

winter of 1881-82, van Gogh took a pregnant prostitute whom he called Sien into his

lodgings in the Hague and cared for her. Van Gogh's family, not surprisingly,

disapproved. It was to Zola that he turned for his defense in a letter to Theo.

"I am glad that you have been reading Le Ventre de Paris; lately I read Nana too. I just want to ask you what you think of Mme Francois, who lifted poor Florent into her cart and took him home when he was lying unconscious in the middle of the road where the greengrocers' carts were passing. Though the other greengrocers cried, Let that drunkard lie, we have no time to pick men up out of the gutter, etc. That figure of Mme Francois stands out so calmly and nobly and sympathetically all through the book, against the background of the Halles, in contrast with the brutal egoism of the other women. See, Theo, I think Mme Francois is truly humane; and I have done, and will do, for Sien what I think someone like Mme Francois would have done for Florent if he had not loved politics more than her. Look here, that humanity is the salt of life; I should not care to live without it, that's all."28 That Emile Zola had influence over Vincent van Gogh is obvious from the sheer number of references the painter made to the artist. Van Gogh saw Zola as a kindred spirit regarding the social purpose of art as well as the artistic interpretation of reality. Van Gogh drew comfort from Zola's understanding of the struggles that artists endured. And on at least one occasion, the artist used the writer's words to defend his personal life. If Zola (and his modern ilk) did not turn van Gogh away from the Bible per se, the artist did interpret the Bible through the lenses which the Zolas and Hugos of the nineteenth century provided. Clearly, Zola's influence upon van Gogh was enormous.

Footnotes

1 Kathleen Powers Erickson, At Eternity's Gate: The Spiritual Vision of Vincent van Gogh (Grand Rapids, Mich.: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1998), 9, 37, 55-56. 2 The Complete Letters of Vincent Van Gogh, (Greenwich, Conn.: New York Graphic Society, 1958), vol. 1, p. 26, lt. 26. Henceforth cited as Letters. 3 Letters, vol 1, p. 36, lt. 39. 4 Letters, vol. 1, p. 41, lt. 42. ¥ See also Erickson, Eternity's Gate, 81. 5 Erickson, Eternity's Gate, 37. ¥ Letters, vol. 1, p. 41, lt. 42. 6 Further Letters of Vincent Van Gogh: 1886-1889 (London: Constable & Co., 1929), 317. Henceforth cited as Further letters. 7 Letters, vol. 1, p. 194, lt. 133. ¥ Cliff Edwards, Van Gogh and God: A Creative Spiritual Quest. (Chicago: Loyola University Press), 52-53. 8 Quoted in Erickson, Eternity's Gate, 90. 9 André Krauss, Vincent Van Gogh: Studies in the Social Aspects of his Work (Tel Aviv, Zmora Bitan, 1983), 138. 10 Erickson, Eternity's Gate, 180. See also ibid., 93, 100. 11 Isaiah 53.3-5, King James Version. 12 Edwards, Van Gogh and God,47-48. ¥ Erickson, Eternity's Gate, 94-95. 13 Erickson, Eternity's Gate, 94. 14 Edwards, Van Gogh and God,52. ¥ Erickson sees van Gogh's sentiments here as expressing the desire to use "the French naturalists, including Zola, as a supplement to the foundation he gained from reading the Bible." Erickson, Eternity's Gate, 93. 15 Quoted in Edwards, Van Gogh and God,181-2. 16 Letters, vol 1, p. 421, lt. 219. 17 Letters, vol 2, p. 260, lt. 355. 18 Further letters, p. 50, lt. 482. 19 Further letters, p. 137, lt. 519. 20 Erickson, Eternity's Gate, 134. 21 For a discussion of Van Gogh's religious upbringing, see Erickson, Eternity's Gate, 9-35. 22 Krauss, Social Aspects, 13. 23 Erickson, Eternity's Gate, 86-88 24 Further letters, p. 140, lt. 520. 25 Krauss, Social Aspects, 14. 26 Letters, vol 2, pp. 427-8, lt. 429. 27 Further letters, pp. 152-153, lt. 524. 28 Letters, vol 1, pp. 418-419, lt. 219.

Return to Visitor Submissions page

Return to Visitor Submissions page

Return to main Van Gogh Gallery page

Return to main Van Gogh Gallery page