![]()

By Louis van Tilborgh

The Van Gogh Museum

The painting Van Gogh made in 1885 was his first attempt to produce a masterwork which would establish his reputation. Having barely mastered the art of painting, the task he set himself was virtually beyond his reach. Portraying five figures and making them look natural is impossible for an unpracticed hand, while achieving the effects of light cast by an oil lamp made the project even more difficult. His use of colour was no less ambitious, for he wanted to render a gloomy interior as brightly as possible.

Van Gogh had made preparations well in advance. He produced numerous portrait studies and several composition sketches in charcoal and oil before tackling the definitive canvas.

The Potato Eaters is the deliberate attempt of an eager young artist to prove himself to the world after five years of study. Intent on producing a mature figure piece, Van Gogh had resigned himself to the fact that his first test of strength in his ambitious genre would not be without imperfections. Even in 1883, during his time in The Hague, when he had barely mastered the rudiments of painting, Vincent was hoping to produce a figure

piece that would proclaim his talent to colleagues, connoisseurs and dealers. The Potato Diggers, which he started in August of that year, marked his first attempt at a large composition. But his desire to make an impression proved greater than his skill, for he abandoned the project after making the first rough sketch.

The Potato Eaters is the deliberate attempt of an eager young artist to prove himself to the world after five years of study. Intent on producing a mature figure piece, Van Gogh had resigned himself to the fact that his first test of strength in his ambitious genre would not be without imperfections. Even in 1883, during his time in The Hague, when he had barely mastered the rudiments of painting, Vincent was hoping to produce a figure

piece that would proclaim his talent to colleagues, connoisseurs and dealers. The Potato Diggers, which he started in August of that year, marked his first attempt at a large composition. But his desire to make an impression proved greater than his skill, for he abandoned the project after making the first rough sketch.

In Nuenen, too, where he settled at the end of 1883, the goal of creating a mature composition with several figures continued to elude him, his only works with more than one figure were the large designs he was commissioned to make for the dining room of his friend Hermans. He had photographs taken of some of these sketches but seems to have been not satisfied with his efforts. In any event, nothing came of his plans to work the sketches into finished paintings (462, 377). His courage appears to have failed him, and the fact that he confined himself to a design with two or three figures instead of the five or six that Hermans had wanted reflects the way Van Gogh himself rated his artistic capabilities at the time (460, R48).

Although he still lacked confidence in his ability to compose figure pieces, he was generally more satisfied with his studies from life. Hoping to augment his meagre income, he even contemplated "shaving [his] work, launching it in

public", as he wrote in February, 1884 (430; 360). He consulted his brother on the matter, only to discover to his anger and disappointment that Theo was less than enthusiastic about the quality of his recent work. Moreover, his brother was merely a junior at the influential Goupil & Co., and as such had reservations about promoting

Vincent's still immature work.

Although he still lacked confidence in his ability to compose figure pieces, he was generally more satisfied with his studies from life. Hoping to augment his meagre income, he even contemplated "shaving [his] work, launching it in

public", as he wrote in February, 1884 (430; 360). He consulted his brother on the matter, only to discover to his anger and disappointment that Theo was less than enthusiastic about the quality of his recent work. Moreover, his brother was merely a junior at the influential Goupil & Co., and as such had reservations about promoting

Vincent's still immature work.

Vincent's painting continued to improve in the course of 1884. His palette became "more solid and more precise" and his technique increasingly personal. He therefore found it all the more difficult to accept his brother's rebuffs (470; 384). Without Theo's help he had little chance of making a successful entrée into the art market. He sent him photographs of his recent figure pieces, and wrote several letters complaining that financial help without moral support was useless, and indeed downright cruel.

Theo then went to the opposite extreme, for at the beginning of March 1885, he asked the astonished Vincent whether he had any work to submit for the Paris Salon that year (488; 395). He had grown weary of Vincent's constant complaints, and was probably hoping to salvage their rapidly deteriorating relationship. Their interests conflicted, however, and his proposal to enter Vincent's best works for the Salon was in fact a subtle and tactful compromise. It gave Vincent an opportunity to prove himself, without Theo having to risk his good name at Goupil's. All he had to do was submit the work; the rest was up to the jury of the Salon.

Eager as he was to embark on his true career and grateful for Theo's encouragement, Vincent nevertheless felt he had nothing worth sending. But the gesture had restored his self-confidence, and he wrote back shortly afterwards, intimating that the portrait studies he had been working on during the past few months were to culminate in an ambitious, structured composition. "As far as I am concerned, I cannot show a single painting yet, nor even a single drawing. But I do make studies, so I can well imagine that the time will come when I will also be able to make compositions. And besides, it is difficult to say where the study ends and the actual painting begins. I am considering a

few worked out pieces […] like figures against the light of a window, for instance" (489; 396).

Eager as he was to embark on his true career and grateful for Theo's encouragement, Vincent nevertheless felt he had nothing worth sending. But the gesture had restored his self-confidence, and he wrote back shortly afterwards, intimating that the portrait studies he had been working on during the past few months were to culminate in an ambitious, structured composition. "As far as I am concerned, I cannot show a single painting yet, nor even a single drawing. But I do make studies, so I can well imagine that the time will come when I will also be able to make compositions. And besides, it is difficult to say where the study ends and the actual painting begins. I am considering a

few worked out pieces […] like figures against the light of a window, for instance" (489; 396).

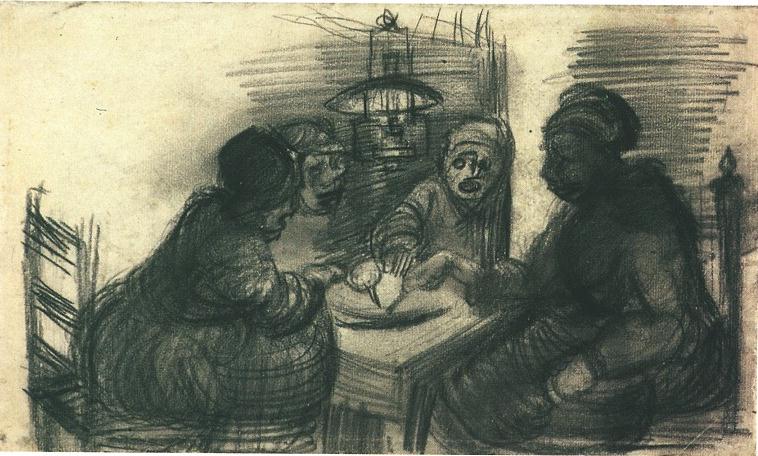

Studies

Vincent must have made the first sketches for his "peasants around a platter of potatoes" soon after writing this letter (493; 398). Shortly after embarking on the project he sent Theo an example, probably a small, spontaneous oil sketch of the composition. Although the exact date on which he sent it was uncertain, he was evidently working on the subject before his father's death on 26 March, as we can deduce from their correspondence that Theo had seen an early proof of the peasant family eating potatoes before leaving Paris for the funeral (493; 398).

Early in April, Van Gogh resumed his work on the motif of the peasant meal; "Whether or not this succeeds," he announced, "I am going to start on the studies for each of these figures"" (493; 398). In the space of three days, some time between about 6 and 13 April, he made the large study which is now at the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo. He enclosed a sketch of the composition in one of his letters to Theo, and sent him a second, quick "scribble" once it was finished (496; 400).

His first uninhibited oil sketch seems to be a faithful representation of the scene to real life. In the new work, however, he altered the composition and added a fifth figure to the original four. At the same time, he introduced a new theme by showing the group drinking coffee, or, more accurately, a brew made from chicory. Like the oil sketch, the second sketch is primarily a study in clair-obscur, although the paint has been applied roughly and with little definition. "I have not been able to work it out as well as I intended", Vincent confessed in a letter to his brother (496; 400).

The second sketch was made inside the peasant cottage, and Van Gogh felt that he had managed to capture the vitality he wanted in a study from life. He was justifiably proud of his first attempt at a structured composition. "At the point which I have now reached", he explained to his brother, "I should be able to give a true impression of what I see". Despite its defects he continued, the work had

'a certain life in it" (495; 399 AND 497; 401). Though Vincent had made progress since his slightly contrived, academic sketches for Herman's dining room, the real test of his strength still lay ahead. He had yet to master the difficult task of working a sketch into a fully-fledged painting, a true tableau., polished in the studio without losing the freshness of the first impression from life.

The second sketch was made inside the peasant cottage, and Van Gogh felt that he had managed to capture the vitality he wanted in a study from life. He was justifiably proud of his first attempt at a structured composition. "At the point which I have now reached", he explained to his brother, "I should be able to give a true impression of what I see". Despite its defects he continued, the work had

'a certain life in it" (495; 399 AND 497; 401). Though Vincent had made progress since his slightly contrived, academic sketches for Herman's dining room, the real test of his strength still lay ahead. He had yet to master the difficult task of working a sketch into a fully-fledged painting, a true tableau., polished in the studio without losing the freshness of the first impression from life.

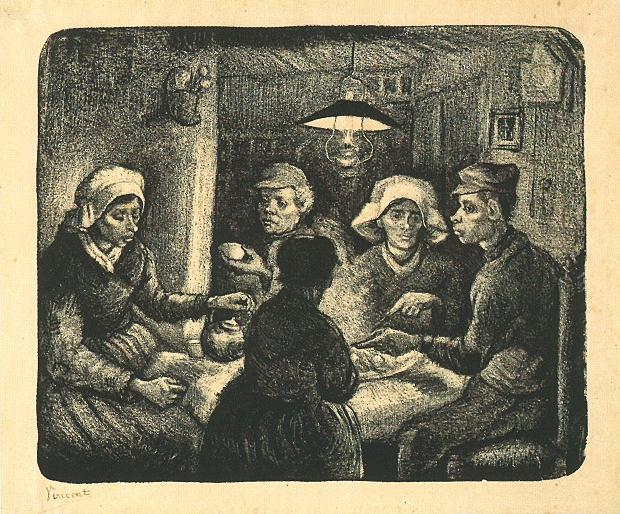

As soon as the second sketch was finished, he made a lithograph of it in reverse. He sent a number of prints to Theo (with explicit instructions to forward several to the Parisian art dealer Portier) and to his colleague Anthon van Rappard. Some time later he also sent a few to the Amsterdam dealer Van Wisselingh. His decision to do so is hard to explain. Proud though he was of the result he had achieved, it made little sense to send reproductions of a study whilst he was still planning to make a final version of the piece. The lithograph was evidently not meant to proclaim the accomplishment of the sketch, but to announce that the final painting was soon to follow. Flushed with triumph, he decided to advertise the masterwork he had not even begun. The letter to Theo which accompanied the lithographs optimistically predicted that the final work 'would perhaps be one that Portier could display, or that we could send to an exhibition' (497,401).

At some point between 13 April and the beginning of May, Van Gogh completed the 'actual' painting. He used an even larger canvas, and referred to it as The

Potato Eaters (501, 404). Unlike the sketch, it was not painted directly from life, but at the Nuenen home of the sexton Schafrat, where Van Gogh had his studio. He rendered it 'mainly from memory', for in the best academic tradition, the budding artist wanted to demonstrate that, besides being able to make a faithful reproduction of what he say, he possessed the rare gift of imagination (501; 404). He only used studies for the faces, and returned to the cottage on an evening to touch up 'a few bits on the spot'.

At some point between 13 April and the beginning of May, Van Gogh completed the 'actual' painting. He used an even larger canvas, and referred to it as The

Potato Eaters (501, 404). Unlike the sketch, it was not painted directly from life, but at the Nuenen home of the sexton Schafrat, where Van Gogh had his studio. He rendered it 'mainly from memory', for in the best academic tradition, the budding artist wanted to demonstrate that, besides being able to make a faithful reproduction of what he say, he possessed the rare gift of imagination (501; 404). He only used studies for the faces, and returned to the cottage on an evening to touch up 'a few bits on the spot'.

At the end of April, Van Gogh took The Potato Eaters to his friend Kerssemakers in Eindhoven. Using a fine brush, he made a few changes to the work between about 2 and 4 May (501; 404). He then too the canvas back to Nuenen, and worked on it once more with the same type of brush. He was apparently struggling to achieve a technically competent piece without detracting from its spontaneity, for he returned to the cottage yet again and retouched the canvas 'from life' (502; 405). At this point, desperately anxious to hear Theo's opinion, he abandoned his plan to make a lithograph after the new piece and, on 6 May, packed the barely dry canvas in a flat crate and dispatched it to his brother (504; 407).

Criticism

The project that Vincent had pinned his hopes on proved less successful than he had anticipated. The Potato Eaters was not exhibited at the Salon, nor did Theo show it to the influential art dealer Durand-Ruel, as Vincent had impulsively requested (501; 404). The only people who are known to have seen it are Theo's neighbour, Alphonse Portier, an enthusiastic rather than successful art dealer in Impressionist work, and an older artist friend, Charles Serret.

According to Kerssemakers, an acquaintance of Vincent's from Eindhoven, Theo took a favourable view of the piece, for 'a few days after sending that sombre painting […] to his brother in Paris, he [Vincent] told me in great excitement that his brother had written about it in the most favourable terms, and he was naturally filled with delight. His brother had said that just by looking at the painting one could hear the clogs of the sittings clacking together, which was of course grist to his mill'. Yet all that emerges from Vincent's correspondence is that Theo made a number of critical remarks and thought the torsos of the figures worse than the heads (522; 418).

Serret and Portier cared little for the murky tone and colours, which were indeed unusually dark by French standards. 'Yet I am content', Vincent wrote, 'that they nevertheless saw some merit in it' (509; 410). The response from Paris was critical rather than complimentary, but Vincent was feeling quite confident. Though his high expectations had not been met, the enterprise was not a complete failure. As Theo later wrote to his mother, Serret has described Vincent's works as immature but promising. In another letter he continued: 'Painters in particular consider it promising. Some see beauty in it, precisely because the characters are so genuine. For it is true that toil and poverty have left their mark on most of the peasants in Brabant, and their faces are hard rather than pleasing'. Such remarks strengthened Vincent's faith in both his artistic and financial prospects. He had already taken the first steps towards establishing contacts in the art market, and now simply needed to consolidate them, certain that it would 'not be very long before we can show more important things.' (522; 418).

Serret and Portier cared little for the murky tone and colours, which were indeed unusually dark by French standards. 'Yet I am content', Vincent wrote, 'that they nevertheless saw some merit in it' (509; 410). The response from Paris was critical rather than complimentary, but Vincent was feeling quite confident. Though his high expectations had not been met, the enterprise was not a complete failure. As Theo later wrote to his mother, Serret has described Vincent's works as immature but promising. In another letter he continued: 'Painters in particular consider it promising. Some see beauty in it, precisely because the characters are so genuine. For it is true that toil and poverty have left their mark on most of the peasants in Brabant, and their faces are hard rather than pleasing'. Such remarks strengthened Vincent's faith in both his artistic and financial prospects. He had already taken the first steps towards establishing contacts in the art market, and now simply needed to consolidate them, certain that it would 'not be very long before we can show more important things.' (522; 418).

The only thing that marred his optimism about the future was the relentless criticism from his friend Van Rappard, whose withering response has become almost legendary. 'You will agree that such work is not serious. You can do better than this--fortunately. But then why have you observed and treated everything so superficially? Why didn't you study the movements? They look so posed. That genteel hand of the woman in the back is completely unrealistic! And what connection is there between the coffee kettle, the table and the hand lying on top of the coffee pot? […] And you dare to invoke the names of Millet and Breton in connection with such work? Art is too lofty, I think, to be treated so lightly.' (529; R57).

In short, the commitment it expressed was more important than the way it was rendered. Vincent's views on what art could achieve were coloured by the naïve and rather bookish notions of his religious past, and even after deciding to make a career in painting, he tended not to distinguish between art and literature. Although he took paints to improve his skills, he continued to attach little importance to technique throughout his time in Holland. In his own words, the true purpose of a painting was to 'inspire [people] to feel or think' (503; 406) and it was for this reason that he rose to the defence of Jozef Israëls Alone in the World and Past Mother's Grave (Amsterdam, Stedelijk Museum) after a visit to Amsterdam in early October 1885: 'Let them prattle on about technique as much as they like in their pharisaic, hollow, hypocritical terms--true painters are guided by the consciousness known as sentiment. Their souls, their minds are not their for the brush, the brush is there for their minds' (537; 426).

His overriding aim was to express the human spirit. Van Gogh had previously attempted to do so in figure drawings such as The Bearers of the Burdern, Worm Out and At Eternity's Gate, but The Potato Eaters was the first painting in which he sought to achieve this. Although he did not give it a similarly anecdotal or explanatory title, his portrayal of a peasant meal was designed to evoke the same type of emotional response to the human condition. To his way of thinking, the artistic value of the canvas lay not in its technical quality, but in the sincerity and fervour of his commitment. This explains his unmitigated rage at the criticism levelled by Van Rappard, for he felt that his friend had missed the point and had failed to understand him.

Physiognomy

Van Gogh explained his views on the painting in a letter to Theo. 'I wanted to convey the idea that the people eating potatoes by the light of an oil lamp used the same hands with which they take food from the plate to work the land, that they have toiled with their hands--that they have earned their food by honest means' (501; 404). This idea may have been inspired by a well-known passage in Jean de La Bruyère's Les caractères de Théophraste of 1688, describing the characters of various human 'types'. Van Gogh had not read the original, but knew the passage from Alfred Sensier's La vie et l'oeuvre de J.F. Millet. Sensier had quoted the excerpt with reference to Millet's Man with the Hoe, which he saw as a representation of 'the shocking passage from La Bruyère: 'One sees a kind of wild animal, male and female, all over the countryside, black, drab and scorched by the sun, bound to the soil which they dig and work with obstinate resolve; they speak with a single voice, and when they rise to their feet they reveal human faces, and they are indeed human. At night they retreat into caves where they live on black bread, water and roots; they spare others the effort of sowing, tilling and harvesting in order to live, and should therefore not want of the bread they have sown'.

In contrast to Millet's Man with the Hoe, Van Gogh's Potato Eaters is an attempt to breathe life into the peasants' untamed expressions within the setting of their own homes. Their baseness, their feral nature, was crucial to the picture's meaning, which is what Van Gogh was trying to convey when he described the canvas as a 'real peasant painting'. 'But if people prefer to see them with a sugar coating, let them. I personally believe that it is better in the long run to paint them vulgar as they are than to give them a conventional charm' (501; 404).

Van Gogh wanted to express that lack of refinement not only in the hands, roughened by work, but even more in the faces, as Millet had done. According to Sensier Millet had in later life been preoccupied with 'the study of human types, the significance of physiognomy'. He was struck by the 'ugliness' of country people and 'did not shrink from depicting coarse-looking faces in his rustic compositions, unrefined, or at best uncultivated figures, whose expressions seem to affirm that human beings are not always superior to animals'.

Gross, brutish, coarse and ugly. This is how Van Gogh wanted to portray his Brabant peasants. As a friend once observed, he made a point of selecting 'the ugliest of them as models'. In Nuenen he had portrayed a woman with the expression of 'a lowing cow' (509; 410). He sought out models with 'coarse, flat faces, with low foreheads and thick lips, not sharp ones, but full and Millet-ish' (454; 372), corresponding to the stereotypes he

had read about in the theories of Gall and Lavater. In their view, fleshy lips betrayed 'a high degree of coarseness and an element of cunning', while in combination with prominent

cheekbones, they were characteristic of the prototypical African, 'a person devoid of intelligence'. A flat face, 'the upper half almost entirely without curves', and a low brow were the signs of a 'stupidity stemming from obduracy, with very little sensitivity'.

Gross, brutish, coarse and ugly. This is how Van Gogh wanted to portray his Brabant peasants. As a friend once observed, he made a point of selecting 'the ugliest of them as models'. In Nuenen he had portrayed a woman with the expression of 'a lowing cow' (509; 410). He sought out models with 'coarse, flat faces, with low foreheads and thick lips, not sharp ones, but full and Millet-ish' (454; 372), corresponding to the stereotypes he

had read about in the theories of Gall and Lavater. In their view, fleshy lips betrayed 'a high degree of coarseness and an element of cunning', while in combination with prominent

cheekbones, they were characteristic of the prototypical African, 'a person devoid of intelligence'. A flat face, 'the upper half almost entirely without curves', and a low brow were the signs of a 'stupidity stemming from obduracy, with very little sensitivity'.

These features--thick lips, protruding cheekbones and low, flat foreheads--can be seen in all Van Gogh's portraits of peasants, as well as in the figures of The Potato Eaters. Their mouths and cheekbones are exaggerated. The woman on the right in the painting and the man on the left with the flat brow and protruding ears, are little more than grotesque caricatures. Other striking features are the wide-open eyes of the two figures on the left, both of whom also appear in Van Gogh's individual portraits of country peasants. The enormous eyes were presumably intended to convey 'the extremes of the animal (…) eye; they are incapable of expression except for the occasional look of surprise, devoid of intelligence. It is impossible to reading anything else in them; such eyes never betray a single thought'.

This emphasis on the feral nature of the characters in The Potato Eaters, Van Gogh insisted, was not intended to malign them. He simply saw them as typical of country people. In short, the painting was an attempt to portray peasants at their purest and most primitive, as representing the ancient, traditional values of rural life. Like animals, they lived in harmony with their unspoiled, natural environment, and it was this that Van Gogh admired.

Louis van Tilborgh

| This article has been reproduced with the kind permission of Waanders Publishers Zwolle, Louis van Tilborgh and the Van Gogh Museum (Amsterdam). |

![]() Return to the main Van Gogh Gallery page

Return to the main Van Gogh Gallery page